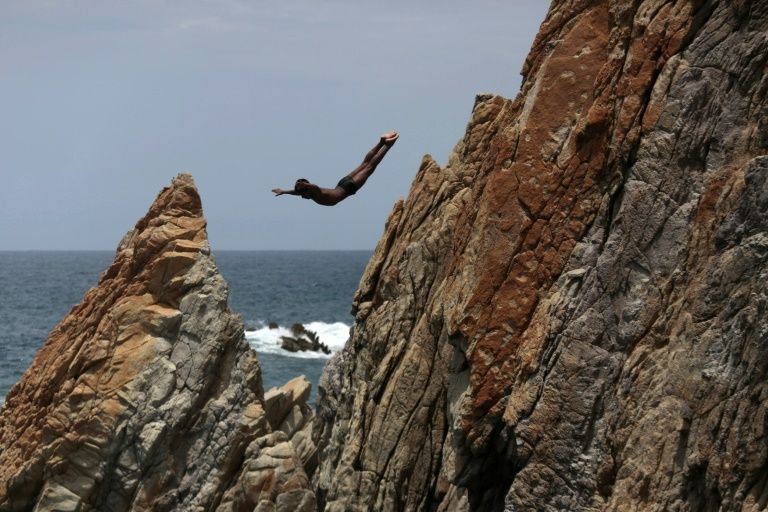

Flahive quotes Henry David Thoreau, the great American essayist and transcendental philosopher who is best known for Walden – a life in the woods and Civil Disobedience: We must walk consciously only part way toward our goal and then leap in the dark to our success. Flahive, his friends and employees all made such leaps and were rewarded with exciting lives, which were all anchored at Salvador’s Coffee House. They left their old lives behind to make a new home in a foreign land and found their place in the modern Chinese dream.

I met the author last summer in Salvador’s Coffee House during my probably last journey to Southwest China, where he gave me his beautifully Klimt-like ornamented book as a present. We both arrived at a similar time about 20 years ago in China and we both ended up in Kunming, he more permanently though. We both got married to truly interesting Chinese countryside girls, and we both try to improve people’s livelihoods with our work. There is a lot we share, above all, I guess our side job as wordsmiths.

Flahive presents a blend between memoir and an applied anthropological study on cause and effect of urbanization: China’s urban migration, now the largest in the history of the world, is fueled by the idea that, regardless of birthplace or social class, cities offer everyone a chance at success. It’s an idea tantamount to that of the American Dream – that people can start with nothing but succeed through hard work alone. Some might argue that in today’s global climate the American Dream is dead, but for hundreds of million in China a similar dream is alive.

While Flahive moved 2004 from Dali to Kunming, I moved 2003 from Kunming to Shanghai, where my then not yet wife studied, then back to Europe and 2009 back to Shanghai. Shanghai is to me probably what Kunming is to Flahive – the city where I have spent so far most years of my adult life – it is my second home. When I describe Shanghai to non-residents, I compare it to New York of the 1970s: it’s the world’s epicenter, the Dragonhead of the world’s largest single market, the cutting edge of commercial and to some extent also social innovation. It’s the place where ambitious young people go in search of their dreams. The American Dream is indeed dead. We now all live our dreams against a Chinese backdrop.

When outsiders hear about urban China, they hear about pollution, overpopulation, heavy traffic, mass consumerism and a blind rush toward modernization. Though all of those characterizations are often what people experience when they come to China, many millions of rural Chinese think of China’s cities in a very different context. For them, cities are the gateways to the modern world. [p169]

Flahive explains through the stories of his employees why they prefer long working hours in Chinese cities to staying in often picturesque villages. Cities are not only gateways to modernity, they are above all gateways to freedom. This phenomenon can only be understood when one applies a longitudinal perspective. China was in many ways until the 1980s stuck in a sort of European middle ages. The delayed onset of the scientific and industrial revolution meant that up till 2011 more than half of the population lived in the countryside as farmers while less than two percent of the labor force in industrialized nations works in agriculture.

The city has therefore a similar value like it had centuries ago in Europe. Kunming has given them the opportunity to look beyond their fate on the farm. It took coming to China for me to learn that cities are more than just consequences of growth. They are places where people can shed their rural shackles to become something more. [p172] School is the one place in the countryside where kids really get a chance to be kids. [p142]

It takes Flahive a while to understand in the narrative of his book why his employees want to trade a life which he seeks, to one he wants to give up. For me, China’s countryside represented the kind of lifestyle I’d always idealized. It was a place where there were no concerns about traffic and pollution – where people’s lives revolved around agriculture and family. The girls had come to Kunming for exactely opposite reasons. For them it was the city that they sought a lifestyle that I had left behind, while I sought a lifestyle that they left behind. [p130]

An explanation can be found in human development psychology and our species’ much underrated learning instinct, which I described in an essay on cities and their evolutionary value as learning spaces. But that’s another story. This one is about why we need to take great leaps if we want to find a fulfilling life. Flahive did it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed