The new functionalities are entirely hidden under the button “钱包 |electronic wallet”, where a new button has been added, which is called “城市服务 | city services”. Shanghainese, it seems can use their wechat accounts from now on to manage even more traditional government services without ever having to enter a government building or talk to a government official. Sadly these functions are mostly not open to Shanghai residents without Shanghai hukou, like myself.

Shanghainese can apply with their wechat account for Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan visa; they can pay their real estate taxes and traffic fines; they can check, if their traffic violations have resulted in a point deduction (if you use up all 12 of them, your license will be revoked); they can buy bus tickets and they can check for stampede threats. In particular the last functionality will be widely welcomed by Shanghai residents after the 2015 CNY tragedy at the Bund. Wechat. What a fancy gadget!

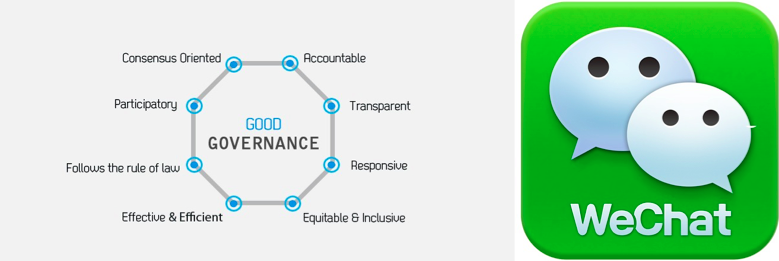

Western good governance think tanks like govlab have been asking for and recommending such services since years. Visionary US author Steven Johnson wrote in two of his books about the huge potential of networked innovation in governance. I have never heard that Chinese did, but here you go. Thanks to Tencent. Or should I rather say: thanks to the massive competition between Tencent, Taobao and Baidu and a cyberleninistic government.

The German think tank merics recently published an article about the battle between these online giants and also organized a workshop about digital mobility. But what do we have in Europe or anywhere else that is comparable? We talk about it, we observe, but there are no or only minimal measures to merge the advantages of the internet revolution with traditional governance in our native economies. Although it must be obvious to the nerdiest government official that it is governance where competition really takes place in the years to come.

Businesses in knowledge economies will to a certain extent have access to all the latest innovations, no matter where they are incorporated. But it is increasingly the dynamics between markets and their governments that will make the difference whether those businesses thrive or fail in global competition. The Chinese internet is still a giant cage like Gady Epstein wrote for The Economist in 2013, but it is a cage it seems that in spite of its limitations makes life easier for those within.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed