Goldenrain Tree | 栾树

At the start of every academic year I have though a very clear indicator for fall, when I walk my children to school. We pass a lane in Jingan district which is decorated by an alley of Goldenrain trees and every fall they start to blossom in thick yellow as if it were spring. Only a week later their flowers begin to “rain” onto the city floor and their fruit leaves turn pinkish red. The combination of green, red and yellow makes this tree a delightful appearance and I enjoy our fall walks to school every morning.

Koelreuteria paniculata is a species of flowering plant in the family Sapindaceae, native to eastern Asia, in China and Korea. It was introduced in Europe 1747, and to America in 1763, and has become a popular landscape tree worldwide. Common names include Goldenrain Tree, Pride of India, China Tree, or varnish tree. While it grows only up to 7m high in the moderate climates of Europe and North America, it turns into a mid-sized up to 20m high tree in subtropical Shanghai.

Without doubt, there are other attractive trees in Shanghai, but they are rather the children of spring. My personal favorite is the Chinese Catalpa or Catalpa ovata, which is native to Western China. The Catalpa tree is an ornamental shade tree that produces dense clusters of white or purple flowers and long seed pods. Plant guides say that it can grow upwards of 7m in height, but I know 30m high trees in my Shanghai neighborhood. The Chinese Catalpa is an astonishing sight when in full bloom and which reminds me substantially of central European chestnut trees.

The long and equally ornamental pods are not edible, but bark and leaves have an extensive medical application. Teas and poultices made from the bark and leaves are often used as laxatives and mild sedatives, and to treat skin wounds and abrasions, infections, snake bites, and even malaria. The Catalpa ovata wood is used to build the underside of the guqin, a classic Chinese instrument.

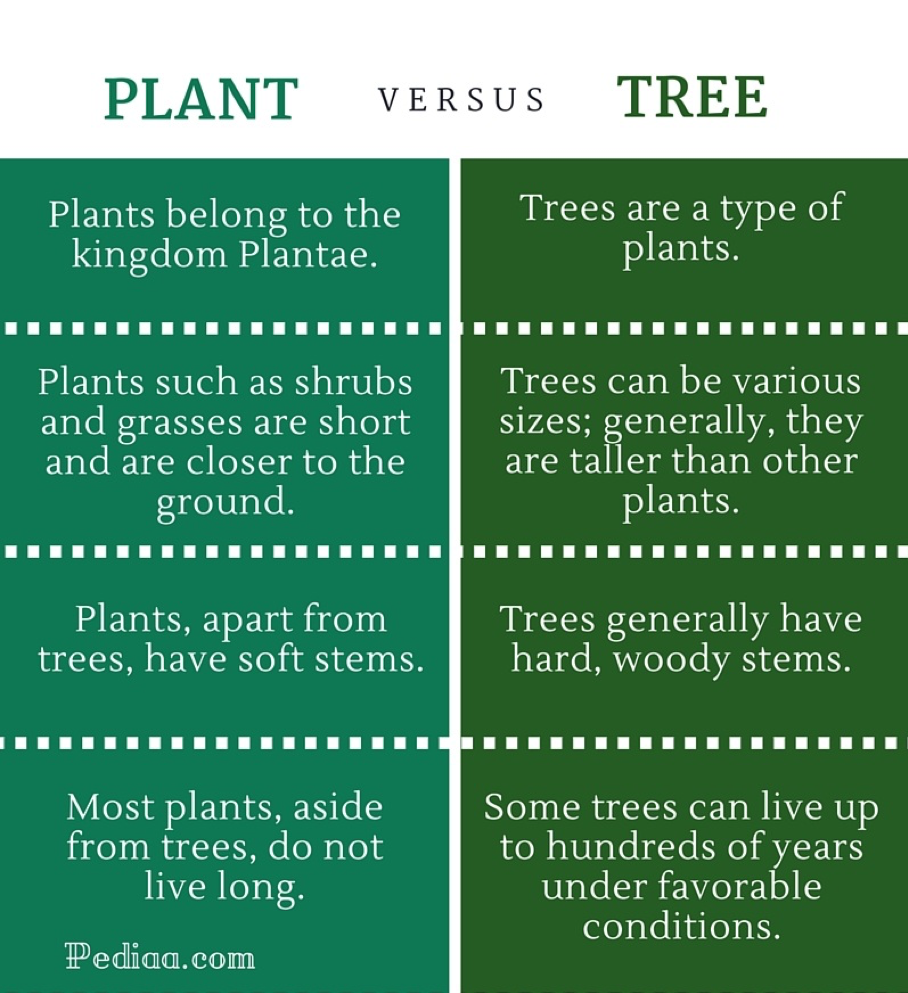

A third contestant for the title Shanghai’s signature tree is certainly the Magnolia, which is also city’s official signature flower for good reasons. However, as below chart explains, a tree and a flower are not the same. Some trees grow flowers, but flowers in themselves are no trees. The arguably most important difference is their life span. While flowers are of very short life, generally only a few weeks, trees can live up to several thousand years.

Like the Chinese catalpa the Magnolia blooms in spring and she does so in breathtaking white and purple. The Magnolia grandiflora is a medium to large evergreen tree which may grow 120 ft (37 m) tall. It typically has a single stem (or trunk) and a pyramidal shape. The leaves are simple and broadly ovate, with smooth margins; they are dark green, stiff and leathery. The large, showy, lemon citronella-scented flowers are white, up to 30 cm across and wildly fragrant, with six to 12 petals with a waxy texture, emerging from the tips of twigs on mature trees in late spring.

Cinnamomum camphora is native to China south of the Yangtze River, Taiwan, southern Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, and has been introduced to many other countries. One could say, the Camphor is a truly Far East Asian tree. It grows up to 20–30 m tall. In Japan, where the tree is called kusunoki, five camphor trees are known with a trunk circumference above 20 m, with the largest individual, the "Great camphor of Kamō"), reaching 24.22 m.

The leaves have a glossy, waxy appearance and smell of camphor when crushed. In spring, it produces bright green foliage with masses of small white flowers. It produces clusters of black, non-edilble, berry-like fruit around 1 cm in diameter. Its pale bark is very rough and fissured vertically. While the tree is compared to the Chinese Catalpa, the Magnolia Grandiflora and the Goldenrain Tree of rather modest appearance, its evergreen foliage produces an enormous variety of colors in all hues of green, yellow and red. Moreover, the Camphor Laurel has since known times been the source of an important culinary and medical substance.

Camphor is a waxy, flammable, transparent solid with a strong aroma, is found in the wood of the Camphor Laurel. It is used for its scent, as an ingredient in cooking, as an embalming fluid, for medicinal purposes, and in religious ceremonies. It was a widely used ingredient in sweets and dessert dishes in medieval Europe, the Arabic world and India; and was a much-coveted substance in early international trade.

The fifth and last tree we explore in this short article about Shanghai’s most common trees is the Paper Mulberry, aka Broussonetia papyrifera. It is native to Asia, where its range includes China, Japan, Korea, Indochina, Burma, and India. Like the Camphor Laurel, the Paper Mulberry is of rather modest appearance and without attractive flowers. Instead of black berries it produces though in fall a fleshy red fruit which gives the tree temporarily a celebrative atmosphere.

While not cherished like the Magnolia as a modern ornamental tree, the Paper Mulberry has been for most of human history farmed like corn or wheat. It was a significant fiber crop in the history of paper. It was used for papermaking in China by around 100 AD, and in Japan to make washi by 600 AD. Washi, a Japanese handcrafted paper, is made with the inner bark, which is pounded and mixed with water to produce a paste, which is dried into sheets.

There is evidence that the Paper Mulberry, which grows on almost all Pacific Islands, was taken from early human settlements in the Pearl River Delta on their journey to the East. Paper Mulberry is primarily used in the Pacific Islands to make barkcloth and was therefore cultivated by Polynesian tribes like life stock. The fruit, leaves, and bark have been used in systems of traditional medicine as a laxative (increase bowel movement) and antipyretic (fever controlling). Without doubt, one could claim that the Paper Mulberry was something like killer app of Neolithic cultures.

There is one more tree which can’t go amiss on a list of Shanghai’s most important trees, the Plane Tree. It decorates many alleys in Shanghai and certainly defines in combination with European architecture the flair of the former French and British concession areas. It is one of the most massive trees of the temperate climate zone growing occasionally up to 50m high. Its size and its large leaves which make the Plane an ideal tree to provide shade in hot urban summers. Its leaves are cause for confusion because their palmate shape make them look similar to Maple leaves.

Plane trees are native to the Americas and to Europe. The American Plane Tree is known as Sycamore, New World Plane or platanus occidentalis. The European Plane Tree is known as platanus orientalis and was originally distributed in an area stretching from the Balkan countries, Greece to Turkey. A third species of Plane tree is widely known as London Plane or Platanus acerifolia. Most modern authorities accept that P. acerifolia is a hybrid between P. orientalis and P. occidentalis. The belief finds support not only in the botanical characters of the London plane but also in its great vigour – a common feature of first-generation hybrids between related species – and in the variability of its seedlings.

While the origin of the London Plane is still debated amongst botanists, there is no doubt that the colloquial name of Shanghai’s plane trees is confusing. Most Shanghainese call the Plane tree 法国梧桐 or French Parasol Tree, most likely because it was introduced to Shanghai, when the city was influenced by its French residents. Considering that the Plane Tree alley in Jingan Park, a former military cemetery, is a natural monument of British rule in Shanghai, one is inclined to assume that Shanghai’s Plane Trees are indeed London Planes, which the British introduced to the city in the 19th century. Wherever they come from, Shanghai’s plane trees are pleasant to the eye and provide excellent shade.

A. Goldenrain Tree 栾树

B. Chinese Catalpa 梓

C. Magnolia Grandiflora 玉兰

D. Camphor Laurel 樟

E. Paper Mulberry 构树

F. Plane Tree 悬铃木

RSS Feed

RSS Feed