This is a review of the above title written by Damian Ma and William Adams, two US American analysts, one of them with Chinese ethnical background. The book was first published in September 2013 and our Shanghai book club has chosen it as the third read in 2015. There was already a discussion of the title on Sinica some weeks ago.

The authors structure their book in three main chapters on which are each divided into 3 subchapters: Economic Scarcity: Resources, Food, Labor. Social Scarcity: Welfare, Education, Housing. Political Scarcity: Ideology, Values, Freedom.

I have felt in our discussion some criticism; there were people who said that the authors are not senior enough; there were others who felt that the last chapter on political scarcity was neither well written nor written in the right place; there were people who said that the book did not bring about any revelation, anything that has not been written before; and above all: the book is to critical of China and therefore censored.

I can not agree. The authors succeed to look at China from the point of scarcity and they do a great job in this. The book is well researched and boasts a huge volume of data, both in numbers and background references. This accomplishment alone deserves some credit, because I can’t remember such a comprehensive book being published on contemporary China during the last few years.

I think though that the title was sort of misleading. In Line Behind a Billion People prompted me to expect a book that would look at the impact of the largest population on this planet along its rise to become the largest per capita consumer. I expected a book that would analyze the economical implications of a rising China on the ROW. The authors look instead beyond the economics and go deep into politics. With all their thoughts they remain in effect hooked on China and do not provide what the title implies: a perspective for the ROW. What does it mean for the West to wait in line behind a billion people? What does it mean that a strong China will first secure resources for its own people and the leftovers will be shared amongst the ROW?

Albeit above questions not answered, Damian Ma and William Adams implicitly show that China suffers from two sorts of scarcity: a natural which is caused by a Malthusian overpopulation and an artificial which is caused by a government whose self interests keepss it from keeping up pace with the changes in society – but lets be honest: isn’t this the case in most societies?

The authors write “China, please slow down. If you’re too fast, you may leave the souls of your people behind … That for all the breathless economic development speeding along at bullet train pace, the public continues to feel that it is being left behind. The Chinese economic miracle that has captured the world’s attention is no longer so compelling to a large portion of Chinese.”

I feel that the authors are not critical after all. They give a 7 out of 10 probability to a scenario in which the Chinese government adapts and responds to the requirements of the society. I am moreover convinced that the intensity with which China changes, both in terms of population and rapid economic development – although things look horrible now – will have a beneficial impact on humanity at large. Nowhere else but in China would it have been possible that all the technologies which we have been using for some decades in industrialized nations are applied on such a scale. If we would not see and feel the negative impact in China, we might continue to use fossil fuels for another 200 years or more. If Chinese solar panels would not have dumped the world price, we would invest less in green energy. If China’s urban centers would not be congested with individual vehicles at a scale which mankind has never seen before, we would not think so fast of other means of transportation.

After all there is a visible hand showing us unconsciously a path forward. And China is an integral part in this path. Many Chinese will and some already do ask themselves although not having tasted all of materialisms pleasures if GDP should not be substitutes with GWB, if more consumption does not equal more destruction. Many go abroad, because of domestic scarcities, some retire to the countryside from where have come – villagers turning urbanites and again villagers within ones own lifespan!

In Line Behind a Billion People was written at the same time as Thomas Piketty’s “Capital in the 21st Century”. Both books combined make more sense, if we want an answer to where scarcity and inequality will take us and how we can try to get the problem under control. Piketty’s central thesis is that when the rate of return on capital (r) is greater than the rate of economic growth (g) over the long term, the result is concentration of wealth, and this unequal distribution of wealth causes social and economic instability. Piketty proposes a global system of progressive wealth taxes to help reduce inequality and avoid the vast majority of wealth coming under the control of a tiny minority.

As long as the Chinese government continues to yield to the interests of its owning class, there will be no progress and more potential instability. As long as there is no redistribution of wealth which entails a human right for affordable shelter, there will be instability looming over the nation-continent. Ma and Adams say: The holy grail of Chinese housing policy seems to be a legitimate nationalized real estate tax, a policy twofer that replaces land sale revenue’s contribution to public finance and keeps property prices in check. But in politics there is no free lunch; demand taxes from your constituency and you can suddenly find yourself beholden to their demands. Can the government credibly manage the inevitable demands that educated and empowered people will have on public spending once they are forced to pay property taxes?

This interaction between real estate owners, between haves, have nots and the governments reminds me strikingly of Barrington Moore’s elaborations of feudalist societies, where the power struggle at the center of monarchies took place between the royalty and the land owning aristocracy. If you taxed the latter too much, the kind had them rallying against him. Has China after all made a step back in history from socialism to feudalism (with Chinese characteristics of course)?

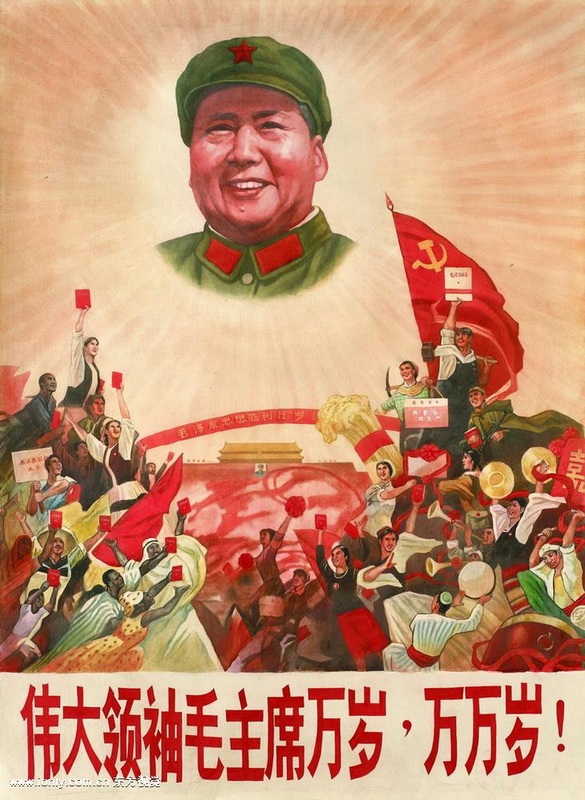

There are more than a few indicators that speak for such a perception of contemporary China. One was given by a Chinese participant of our book club discussion: "The only thing that can save China from cracking up, is a strong leader. Xi Jinping must continue to exert full power during the next years or the system will fail." An absolutist ruler against a feudalist insurgence.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed