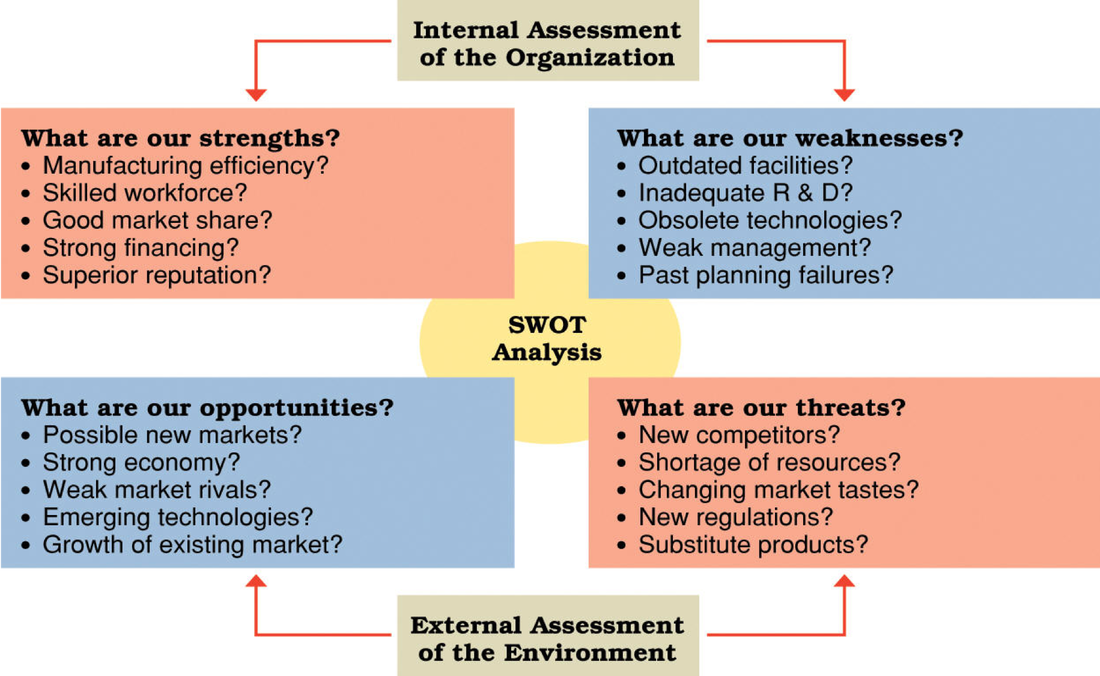

Coming back from Europe only a few days ago, where I showed to our son a modern recycling center in my home town, I have some additional thoughts to share which I have structured in a SWOT analysis, which – nota bene – looks at Shanghai and China at large as an organization with internal strengths and weaknesses and external opportunities and threats.

Back home everything seems to go well. Waste is being separated since about 40 years and recycling has become a habit for most people. It is necessary that such habits are instilled in citizens of emerging economies such as China, but large populations and population density change the dimension of the problem significantly and ask for different and faster solutions.

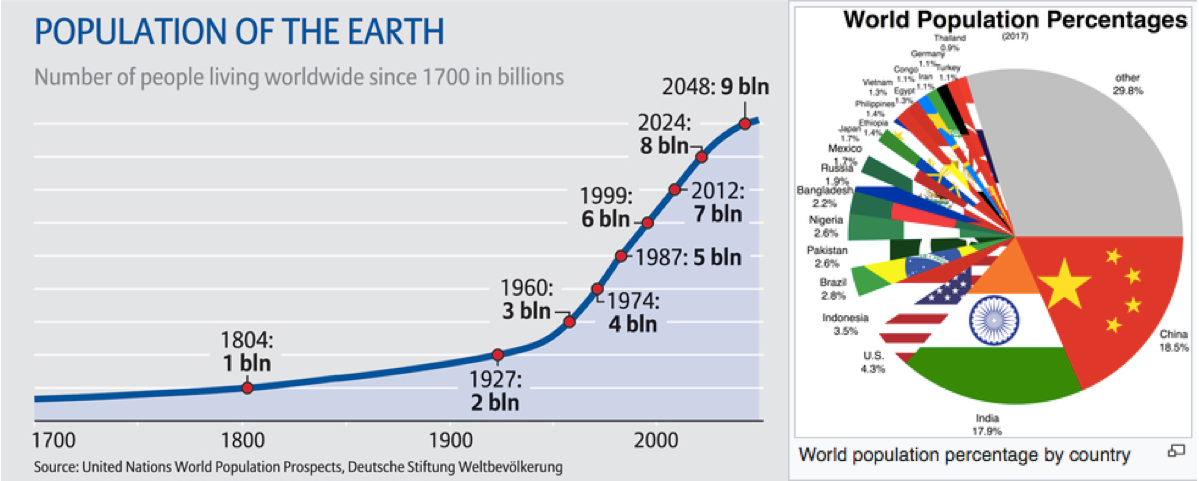

Al Bartlett, a professor emeritus of physics, is the first address to explain why. His somewhat arrogant summary of the problem: "The greatest shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand the exponential function." We deal with two exponential functions at the same time: the first is related to the global population explosion, the second to technological development.

Pixar’s science fiction animation Wall-E has already back in 2008 anticipated the consequences: a deserted waste planet and a tiny (and obese) left over population on a large starship. Entrepreneur Elon Musk doesn’t like science fiction. He wants to prepare for the worst case scenario and builds with SpaceX rockets which shall populate Mars in case we mess up our only home, mother earth.

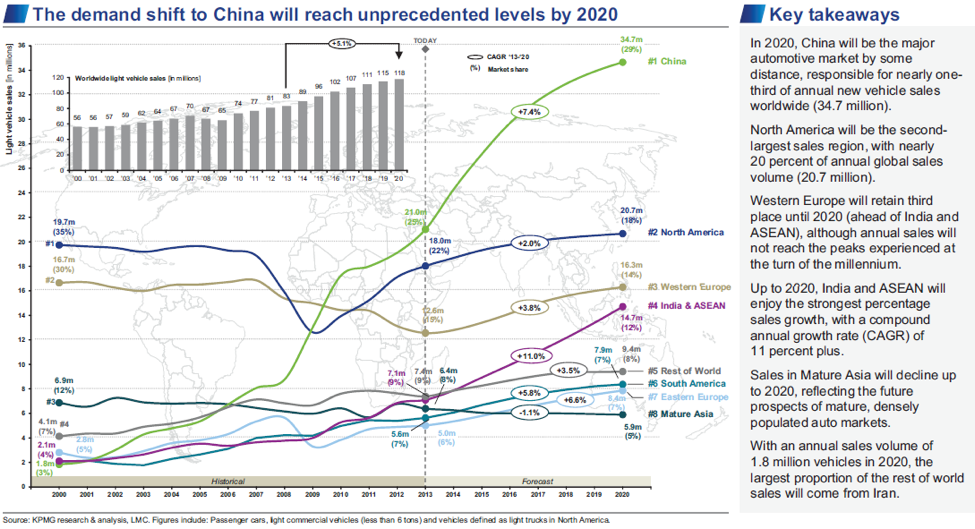

Shanghai’s waste management law comes therefore at a critical moment and it has the potential to catalyze significant global changes. One reason is that Shanghai is China’s dragon head. Whatever gets implemented here, might very likely come as a law for the entire country – and its easy to see from above graph that a success in China’s waste management will be a success for the entire world: China’s population makes up about 1/5 of the total. But think of Shanghai only: roughly 30 million people, that’s approximately the population of countries like Peru, Nepal, Angola or Australia, will get within a few months a completely changed recycling system.

Another strength of this law lies in China’s top down bureaucracy which has a solid track record of successfully coercing its subjects within a short time to unsurmountable tasks. Clear fines for both individuals and companies will be swiftly and most likely without pardon executed by respective public authorities. Shanghai has seen similar measures during the last few years in regard to traffic management, and we know that central leadership wants to emulate Singapore. From such a perspective, there is the possibility that the city if not the entire country turn into a gigantic carbon copy of Japan: spotless tidy and hyper modern.

While these arguments make the law promising, there are weaknesses and even threats – some of them more, some less obvious - which need to be discussed.

It has already been mentioned by several observers that the law will destroy the organically grown informal recycling system. One can question if this informal waste sorting mechanism was really as efficient as described, but it provided a large migrant worker group an additional if not main income. Thinking of some measures which have been implemented during the last three years in Chinese first tier cities, one of the driving motives could be making city life impossible for citizens without Shanghai household registry by depriving them of their source of income. More important though, we need to ask if the new waste management system will be better than the one which is in place.

*

Philosophers ask law makers why they promulgate laws. They call this discipline teleology: the explanation of phenomena in terms of the purpose they serve rather than of the cause by which they arise. Now, Chinese law makers will answer in regard to the waste management law that it had to be promulgated because of rising waste volumes, and it’s purpose is better waste management. So far so good.

The philosopher tends to go a step further in his inquiry and will ask why there is a rise in waste and why there is waste in the first place. Law makers will quickly – but reluctantly – arrive at the conclusion that the increase of overall consumption is the cause of increased waste and need to acknowledge that the law does ignore why we consume.

*

Economists like Valentino Piana from the Economics Webinstitute define consumption as the value of goods and services bought by people. Individual buying acts are aggregated over time and space and constitute collectively the consumption of economies. Consumption is normally the largest GDP component and many judge the economic performance of their country mainly in terms of consumption level and dynamics.

Consumption may be categorized according to the durability of the purchased objects or according to the needs its satisfies. Durable goods (as cars and television sets) are different from non-durable goods (as food) and from services (as restaurant expenditure). These three categories often show different paths of growth. Another commonly used classification identifies ten needs of expenditure:

1. Food

2. Clothing and foot wear

3. Housing

4. Heating and energy

5. Health

6. Transport

7. House furniture and appliances

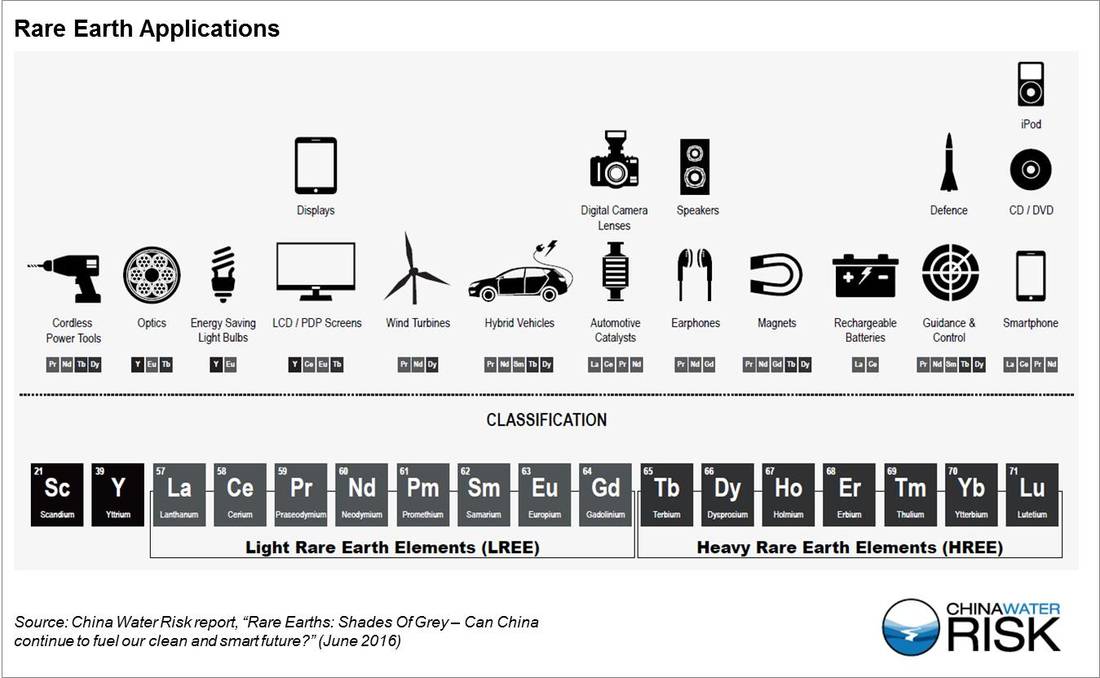

8. Communication

9. Culture and schooling

10. Entertainment

Now, this might sound awkward to you, but from an economist’s perspective more people consuming more health services and medication are good news. The same is true for education: the more parents invest in cram school, the better for the economy. And of course also for the entertainment industry: the more frustrated kids play computer games, the better for the economy. And yes, its also true for food, fashion and cosmetics: the more bags Kitty buys, the fancier the restaurants Cherry dines in, and the more expensive the skin whitener April puts on, the better for the economy.

So, now let’s think of how to dispose of all this stimulating and job-creating consumption.

*

*

Ever since law school I have this probably strange idea that the purpose of laws must be increased well-being and that law makers need to inquire deeply or call upon expert assistance to understand psychosocial dynamics which result in more or less thereof. I contend that this law will not fare well under such an examination.

While we need to implement better waste management not only in China, but also in other parts of the emerging world, we need to ask ourselves simultaneously why we increase consumption and why we generate more and more waste. The documentary The Economics of Happiness provides a straight forward answer: Consumer markets and national entities destroy small and local communities. Increased consumption is therefore the result of a psychological compensation mechanism which has its root in less social interaction.

While above categorization of consumption talks of needs, we must acknowledge that much of what we consume does not satisfy a need but a want which has been instilled by an anonymous consumer society and a mighty advertisement industry. The advertisement industry on the other hand follows the orders of its corporate clients and those are sprockets in the large machinery of state capitalism – a form of governance which requires GDP growth in order to guarantee social stability, i.e. domestic peace.

If we think about the teleology of the waste management law in depth, we must arrive thus at the conclusion that despite its appearance, it is not an environmental but an economic law which intends to bring order into consumption and resulting waste generation with the far end of making more consumption and thus GDP growth possible for an economy which perceives itself separate from the rest of the world.

*

It might be surprising, but this Chinese policy is completely in line with the UN sustainability goals and reverberates the legislation of most industrialized nations. There is the opportunity that those who have been ignorant to the negative consequences of infinite consumption and material growth will wake up when China starts to thread the same path many small economies have been threading before her.

Jason Hickel commented on the flawed UN sustainability goals in an outstanding 2015 article: All of this reflects an emerging awareness of the fact that something about our economic system has gone terribly awry – that the mandatory pursuit of endless industrial growth is chewing through our living planet, producing poverty at a rapid rate, and threatening the basis of our existence.

Yet, despite this growing realization, the core of the SDG program for development and poverty reduction relies precisely on the old model of industrial growth — ever-increasing levels of extraction, production, and consumption. And not just a little bit of growth: they want at least 7 percent annual GDP growth in least developed countries and higher levels of economic productivity across the board. In fact, an entire goal, Goal 8, is devoted to growth, specifically export-oriented growth, in keeping with existing neoliberal models.

This is the mortal flaw at the heart of the SDGs. How can they be calling for both less and more at the same time? True, Goal 8 is peppered with progressive-sounding qualifications: the growth should be inclusive, should promote full employment and decent work, and we should endeavor to decouple growth from environmental degradation. But these qualifications are vague, and the real message that shines through is that GDP growth is all that ultimately matters.

Historian Yuval Harari explains in his book Homo Deus eloquently why economic growth – and thus more consumption – is all that matters and why it has become for all governments, not only the Chinese, the solution to all problems: it has turned into a religion in which we blindly trust.

Modernity has turned ‘more stuff’ into a panacea. […] Economic growth has thus become the crucial juncture where almost all modern religions, ideologies and movements meet. The Soviet Union, with its megalomaniac Five Year Plans, was as obsessed with growth as the most cut-throat American robber baron. Just as Christians and Muslim both believed in heaven, and disagreed only about how to get there, so during the Cold War both capitalists and communists believed in creating heaven on earth through economic growth, and wrangled only about the exact method.

Today Hindu revivalists, pious Muslims, Japanese nationalists and Chinese communists may declare their adherence to very different values and goals, but they have all come to believe that economic growth is the key for realizing their disparate goals.

Japan’s prime minister, the nationalist Shinzo Abe, came to office in 2012 pledging to jolt the Japanese economy out of two decades of stagnation. His aggressive and somewhat unusual measures to achieve this have been nicknamed Abenomics. Meanwhile in neighboring China the Communist Party still pays lip service to traditional Marxist-Leninist ideals, but in practice it is guided by Deng Xiaoping’s famous maxims that ‘development is the only hard truth’ and that ‘it doesn’t matter if a cat is black or white, so long as it catches mice’. Which means in plain language: do anything it takes to promote economic growth, even if Marx and Lenin wouldn’t have been happy with it. In Singapore, as befits that no-nonsense city state, they followed this line of thinking even further, and pegged ministerial salaries to the national GDP. When the Singaporean economy grows, ministers get a raise, as if that is what their job is all about.

That Modi, Erdogan, Abe and Xi Jinping all bet their careers on economic growth testifies to the almost religious status growth has managed to acquire throughout the world. Indeed, it may not be wrong to call the belief in economic growth a religion, because it now purports to solve many if not most of our ethical dilemmas. Since economic growth is allegedly the source of all good things, it encourages people to bury their ethical disagreements and adopt whichever course of action maximizes long term growth. […] The credo of ‘more stuff’ accordingly urges individuals, firms and governments to discount anything that might hamper economic growth, such as preserving social equality, ensuring ecological harmony or honoring your parents. […] Yet is economic growth more important than family bonds? By daring to make such ethical judgments, free-market capitalism has crossed the border from the land of science to that of religion.

Most capitalists probably dislike that title of religion, but as religions go, capitalism can at least hold its head high. Unlike other religions that promise us a pie in the sky, capitalism promises miracles here on earth – and sometimes even provides them. Much of the credit for overcoming famine and plague belongs to the ardent capitalist faith in growth. Capitalism even deserves some kudos for reducing human violence and increasing tolerance and cooperation […] by encouraging people to stop viewing the economy as a zero-sum game, in which your profit is my loss, and instead see a win-win situation, in which your profit is also my profit.

*

Capitalism as a religion is the product of a the age of nationalism and system blindness, one which puts the well-being of a small group of people over the well-being of a superorganism which encompasses this planet and all its creatures. China’s waste management law might well be a catalyst in bringing this awareness to more people, because it will become soon apparent that better organized waste disposal will not prevent life-stock epidemics like the African swine fever from eruption; it will not prevent the exploitation of oceans and the collapse of fish species; it will not stop the destruction of rain forests in favor of monocrop agriculture. No, it will speed up these developments and continue to waste natural resources.

The German-British economist E. F. Schumacher put this idea into unmatched clarity: The illusion of unlimited powers, nourished by astonishing scientific and technological achievements, has produced the concurrent illusion of having solved the problem of production. The latter illusion is based on the failure to distinguish between income and capital where this distinction matters most. Every economist and businessman is familiar with the distinction, and applies it conscientiously and with considerable subtlety to all economic affairs – except where it really matters: namely, the irreplaceable capital which man has not made, but simply found, and without which he can do nothing.”

*

He did return and he brought back something very positive: permaculture. It is not like many believe, a model of farming, but much more an attitude of managing natural resources. Mollison adapted principles from various indigenous cultures and merged them into a new body of knowledge for modern humanity. Apart from a deep understanding how we have to treat the planet and ourselves, his most profound insight remains that we have to shift from consumption to production.

Continued focus on GDP growth will not only destroy the planet but most certainly result in more mental health issues and a future which will oscillate between 1984 and Brave New World: a population of consumers who satisfy their state ordained superficial wants and subdues their most authentic needs.

*

RSS Feed

RSS Feed