*

This is the first book in two decades which I read about China without being in the country myself. As such, I experienced an important change of perspective. Osnos was recommended to me by several people, but I had read too much about China already and felt a deep frustration with the country’s status quo. After having departed from where I felt despite all the challenges at home, it came a few weeks ago back to me, almost as if I had to read it to close a big chapter in my life. Yuanfen as the Chinese say.

I rank Osnos’ account of China on the same level as Edward Luce’s account of India Inspite of the Gods and David Pilling’s account of Japan Bending Adversity. It really is the book which anybody should read who has only time to read one book on modern China. It is free of accounts about the pre-Deng era and refers to Mao Zedong only rarely. But probably because I know China in contrast to India and Japan very well, I felt that Osnos lacks the depth of cultural understanding which make Luce’s and Pilling’s accounts so excellent. It is true what Winston Churchill said: “The farther back you can look, the farther forward you are likely to see.”

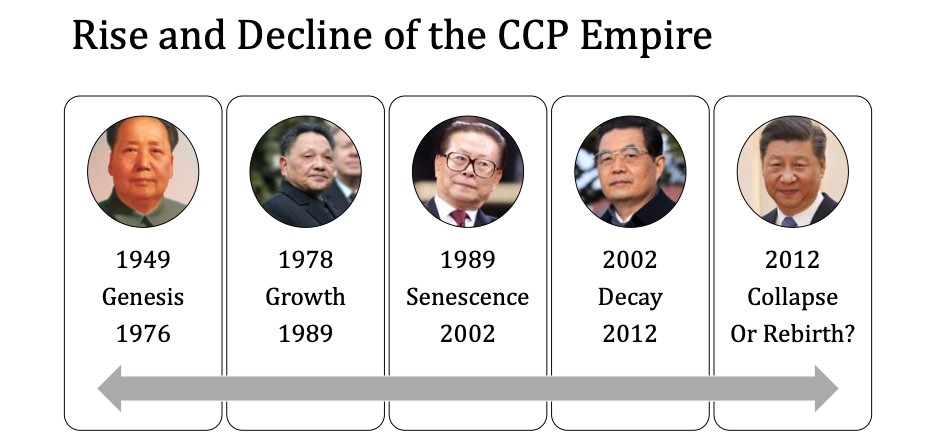

There is good bit of envy. Osnos lived the life which I wanted to live for a while. He worked for the Chicago Tribune and The New Yorker as Beijing based investigative journalist from 2005 to 2013 and witnessed during these years three important events and the surrounding preparations which mark China’s emergence on the world stage and the world’s transition into pax sinica: the Beijing Olympics 2008, the Shanghai World Expo 2010 and Xi Jinping’s ascend to power in 2012. All three of them reflect the ambition of a nation and its leading individual and confirm the perfectly chosen title.

Age of Ambition is structured into three parts - 1. Fortune (p 9-113), 2. Truth (p 117-274) and 3. Faith (p 277-355) - and is eclipsed by a short prologue and a substantial epilogue. Each chapter is eloquently written, and pages keep turning, but it becomes very soon apparent that each chapter is a revised New Yorker article. Osnos stacked his New Yorker stories into three categories to mold this book into a final summary of his China stint. There is nothing wrong with this. I would even argue that the depth of his research for single New Yorker articles improves the quality of the book. Moreover, it would have otherwise not been possible to work both as a full-time staff journalist and churn out Age of Ambition within the little time that Osnos spent in China.

Part 1, Fortune, is really written for those who don’t know China yet and can be skipped by old China hands with the exception of a detailed account on the role of Macao’s casinos in money laundering and capital flight, and the last chapter in which Osnos joins as the only foreigner a guided tour of Europe with Chinese middle-class travelers. It is when Chinese are abroad that they provide the most stunning insights into their own and thus their nation’s psyche, probably best reflected by one of the Lu Xun quotes Osnos uses: Chinese have never looked at foreigners as human beings. We either look up to them as gods or down on them as wild animals.”

Part 2, Truth, oscillates too much around celebrity artist Ai Weiwei, celebrity blogger Hanhan and blind star lawyer Chen Guangcheng. It would have done the book good to portrait some of the struggles which ordinary laobaixing experience when searching for truth. On the other hand, I feel reassured that it was the right thing for me and my family to leave the country – I can’t keep my mouth shut or my pen idle for too long and this trait would have sooner or later inflicted pain on us. I think Jeremy Goldkorn said something similar after he had left the country in 2015.

Part 3, Faith falls short of capturing what faith means in modern China. I certainly recommend reading Ian Johnson’s The Souls of China instead or at least in addition. Part 3 would have been also the place to make a substantial reference to the title in terms of psychological or spiritual motivation. Ambition is quite a tricky word in Buddhist terminology and offers itself to expand upon the spiritual void which is experienced by large parts of the Chinese society. Too much ambition is a form of greed, which causes pain to oneself, others and – as we quite often forget - to the planet. The ecological and psychological damage done by China’s accelerated rise reflects that The Age of Ambition is nothing really great. In its essence it is what caused wars in the past, when kings forget humility and are tempted by hubris.

| age_of_ambition.pdf |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed