To stop short any allegation of China bashing, lets start with the clear statement: there has been done much damage to Africa by Europeans. Mr. French is very outspoken about Africa’s colonial past and the mistakes during four centuries of colonial imperialism. This book is however not about the past, it is about Africa’s present and future, in which Europeans and Americans play a minor, if any role at all. It questions if China’s engagement in Africa is different from European colonialism, and Mr. French goes at great length to show differences and similarities through the interviews with dozens of people in twelve sub-Saharan countries.

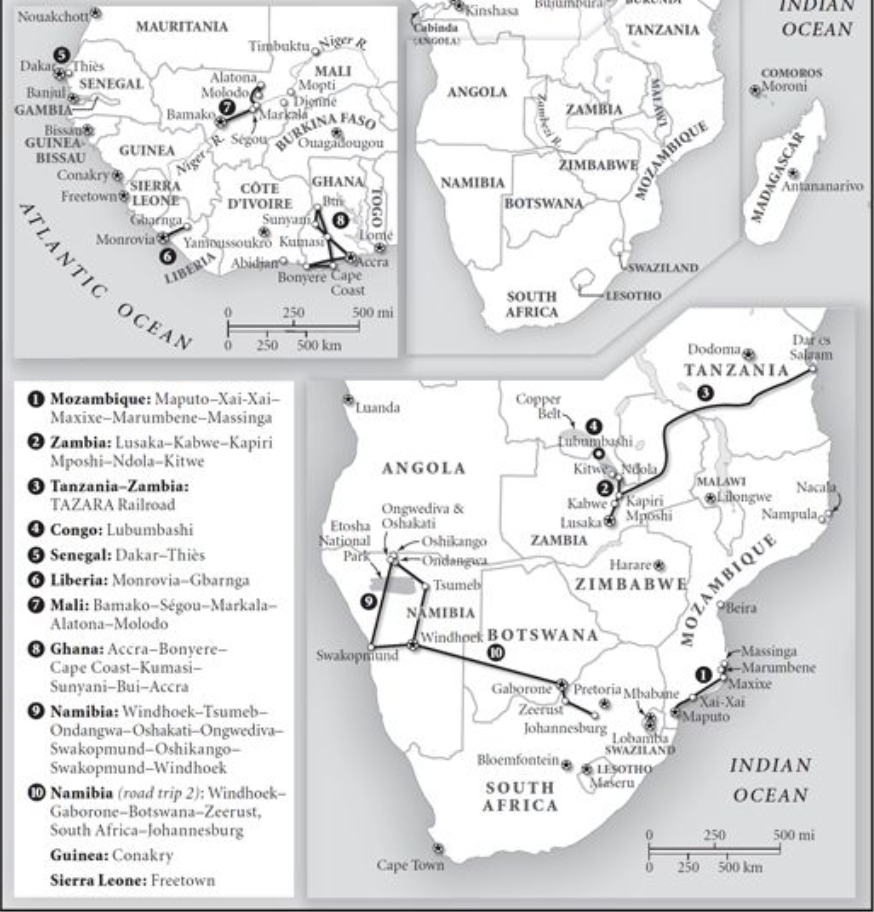

China’s Second Continent is divided in three parts and ten chapters. I was not able to detect any meaningful structure behind the three parts. Each of the chapters is however dedicated to one or two visited countries, and for people like me who know little about sub-Saharan Africa, French provides a readable introduction to colonial and recent history in small bits and pieces strewn in between the interviews with local politicians, NGO professionals, Chinese embassy delegates, state owned company managers and Chinese self-made millionaires.

Despite changing locations, the interviews reveal repeating messages which French resists to summarize in his epilogue, where he focuses on a single question: is China’s engagement in Africa and with Africans different from the colonial imperialism of the past? He comes to the conclusion that it is not and elaborates on three features of imperialism which he confirms with the research on this book.

- Imperialism involves some form of foreign domination, which results in substantially altering the target population or polity; either gradually or suddenly it loses the ability to resist.

- A consistent feature of imperialism is the linkage between political and economic competition among contending powers. And China, for all its denials of any global ambition, is clearly competing with someone and for something – global preeminence.

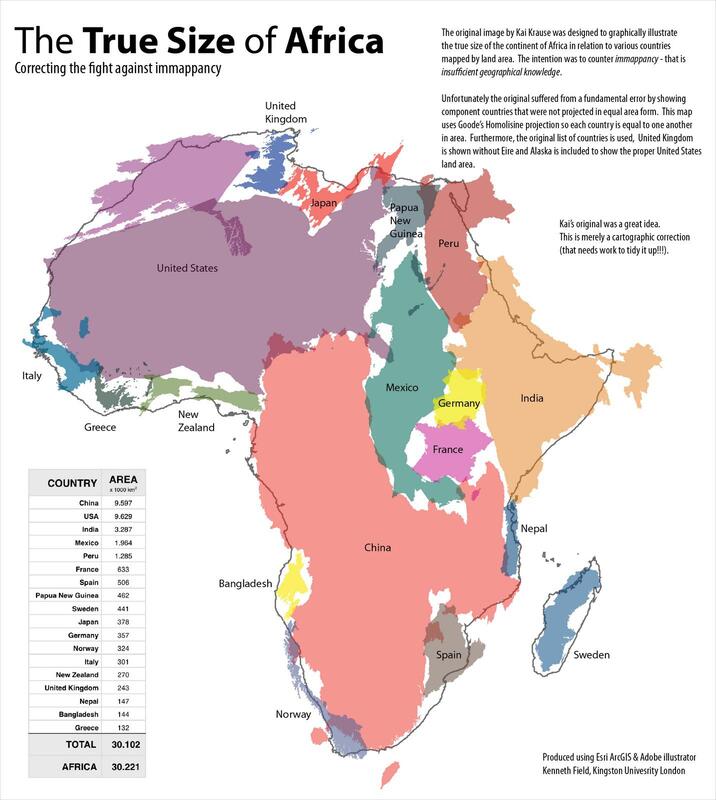

- Migration is the human activity that provides the most striking parallels with imperial patterns of the past. No one knows how many Chinese have set themselves up on African soil in recent years, but if anything, the widely used figure of 1 million seems quite conservative. The arrival of these newcomers on this scale is arguably the lasts chapter in a very long narrative of empire construction through emigration.

All of the above reminds me strikingly of Niall Ferguson’s trilogy on imperialism, which he wrote between 2003 and 2011. It started with the British Empire, continued with the United States as Colossus and ended with an outlook on China’s hegemony in “Civilization: the West and the Rest”. The last book was turned by BBC into a six-episode documentary in which Ferguson shows the imperial transition compellingly by visiting a British built club house in Angola, which is now owned by Chinese. Howard French brings more detail to this Chinese embrace of Africa and creates an unspoken bottom line to global dominance: whoever rules Africa, rules the world.

The dynamics of this nascent pax sinica in Africa and its relevance for issues of global concern like climate change or wildlife biodiversity can be better understood by reviewing and clustering the statements of the author’s interviewees into main takeaways. The question which remains, and which neither French nor I can answer, is how Chinese will respond to their growing responsibility of protecting the world’s most important biodiversity reserves and how they will wield their increasing power over the fastest growing population of any continent. Powers always come with responsibilities; and without doubt, imperial powers contain different responsibilities in the 21st century than they did in the 19th.

- China’s Impact on Africa is not only driven by Beijing

French interviews two groups of Chinese in Africa: One the one hand those employed by the state and state-owned companies who are dispatched to Africa on a collective mission (aka China Dream) of developing foreign markets and gaining access to natural resources, both needed to fuel the home economy. On the other hand, self-employed adventurers who arrive in Africa rather as economic and political fugitives seeking a territory to advance their individual luck outside of the oppressive and overpopulated home society which gives little or no room for social mobility.

French writes about immigrant farmer Hao Shengli: “From spending time with migrants like Hao I learned whether Chinese newcomers had come to Africa to stay, and what their impact would be in transforming African economies, how willing they were to integrate with the locals, and what other impact their massive presence around Africa would have. Unexpectedly, I gained a much deeper understanding of China itself. […] “To be sure, a desire for better economic opportunities was the biggest driver behind their exodus. Still, contributing to the decision for many to take a great leap into the unknown and move to Africa was a weariness with omnipresent official corruption back home, fear of the impact of a badly polluted environment on their health, and a variety of constraints on freedoms, including religion and speech. Many migrants also invoked a sheer lack of space.”

These two groups could also be described as two elements of imperialism. Chinese state-owned companies including Chinese embassies, mirror what the Dutch and British did with their respective East India Companies. Individual migrants however resemble rather the early exodus of British settlers to the United States or Spanish immigrants to South America. Imperialism requires both, a ruling class in the target countries which shares the culture and language with the home country and a political ambition of the home country to dominate the economy of the target country.

Overall, the interviews convey a deeply racist attitude of Chinese towards Africans which I was able to observe also on many occasions in China. If respect and empathy for local cultures and people is the number one precondition to support genuine development and progress, then it is rather unlikely that China’s engagement in Africa serves any other purpose than advancing one’s own interests. French cites a Guinean interviewee: “The Chinese come and they want your iron, your bauxite, your petroleum. In return, they’ll deliver you turnkey projects, where they supply the materials, the technology, and the labor, with salaries that are mostly not paid in the country and do not contribute to the economy.”

It is moreover clear - however one might think about Western development aid to Africa -that there is no interest to genuinely help Africans build their nations into sustainable, self-supporting economies. The statement of Li Jicai, a kind of informal leader of the Chinese community in Senegal is repeated by others in a similar manner: “There is no future in Africa; no future for development,” he said, giving vent to a surprisingly dim worldview. “How will they develop with the kind of education they have here? Look at China. We are putting people into space. We are developing our technologies. We are inventing things and competing with the rich countries. But these people, they are impossible to teach, whether it is how to run a business, or how to build a building, or how to make a road. They just don’t learn.”

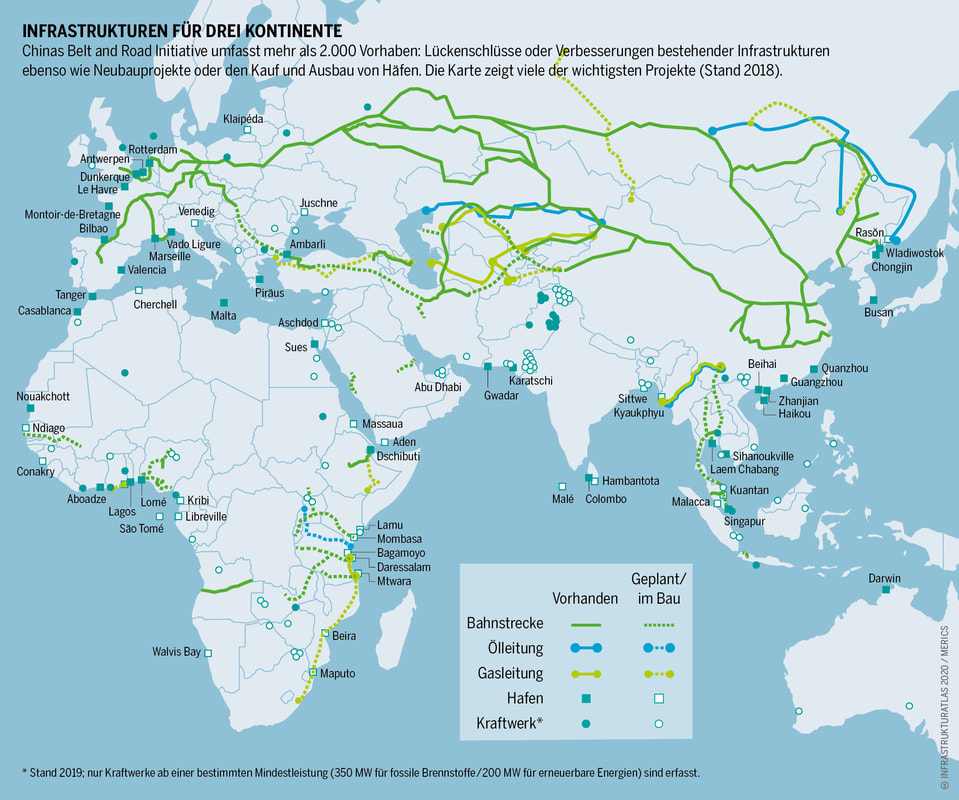

China’s Second Continent, although written already in 2012, is a missing element in the much later announced One Road one Belt Strategy and the more subtle dynamics of state-capitalism. Chinese state-owned companies go into target countries, supercharged with manufacturing equipment and skilled labor in order to compete for large infrastructure projects. The practice of underbidding is described in all of the visited countries as a result of China’s economic imperialism.

French cites Zou Manyang, a project manager for the China Railway Corporation, one of the major road builders in the country. “Underbidding wasn’t just about beating the competition, Zou said, especially the foreign competition. It was about bigger issues, like amortizing heavy equipment costs, and especially about keeping the pumps of China’s enormous public works sector primed. If you have your equipment and your people in place and there is no business, that is very bad. If you bid low, though, even if you have a tiny margin, you are better off. That’s the reason Chinese companies bid low. It’s not because we want more market share. The number of companies and people working in this sector [in China] is very large. We need more and more markets to keep people employed. Most of the companies like mine are state-owned, and if you start laying off workers, it will create huge problems for the country.”

One needs to understand the scale of this systemic imperialism which basically boils down to temptingly easy loans which are mostly pocketed by Chinese state-owned companies. The recipient nations might get football stadiums, roads, bridges and hospitals, but they are deeply indebted, have sold their natural resources for a pittance and created no jobs. Quite on the contrary jobs for the native population are reduced because the deals usually also involve large scale immigration from China destroying local industries like textiles or petty trade.

Another problem which is not explicitly discussed by French is the fact that state capitalism of such global dimension is like a planned economy in which Beijing decides which growth numbers it needs to maintain social stability and sound employment at home. Social stability in China becomes a major benefit of granting shoddy loans to African countries, where corrupt elites get rich fast at the expense of planet and people. China exports an economic system which is highly wasteful, because it does not respond to the needs of the people, but to the needs of China’s industrial machinery and its still largely uneducated consumers.

African leaders, however, are clueless on how to respond to these challenges as Edward Brown, a former employee at the World Bank explains: “I don’t know if the finance ministry has the capacity to assess this kind of deal. And in the office of the president, there is one fellow in charge of the China package.” He amended himself later, to say one or two. “I am not sure there have been any strong analyses of risk management, of finance, of the cost-benefit, of integration into some strategic vision. We really must reach the stage where we can say, You say you want to help us? Let’s talk about what that means, and how we want you to help us. The Chinese, meanwhile, are planning everything down to the letter. They will take whatever they can get from you …

“Will investment [like this] lead to growth that is transformative? Will it lift productivity in your country? Will it halt the decline in important industries, like textiles? Will it launch African production in areas where we have true competitive advantage? How will African countries use it to diversify and transform? Unfortunately, this is a serious intellectual challenge that is not being met.”

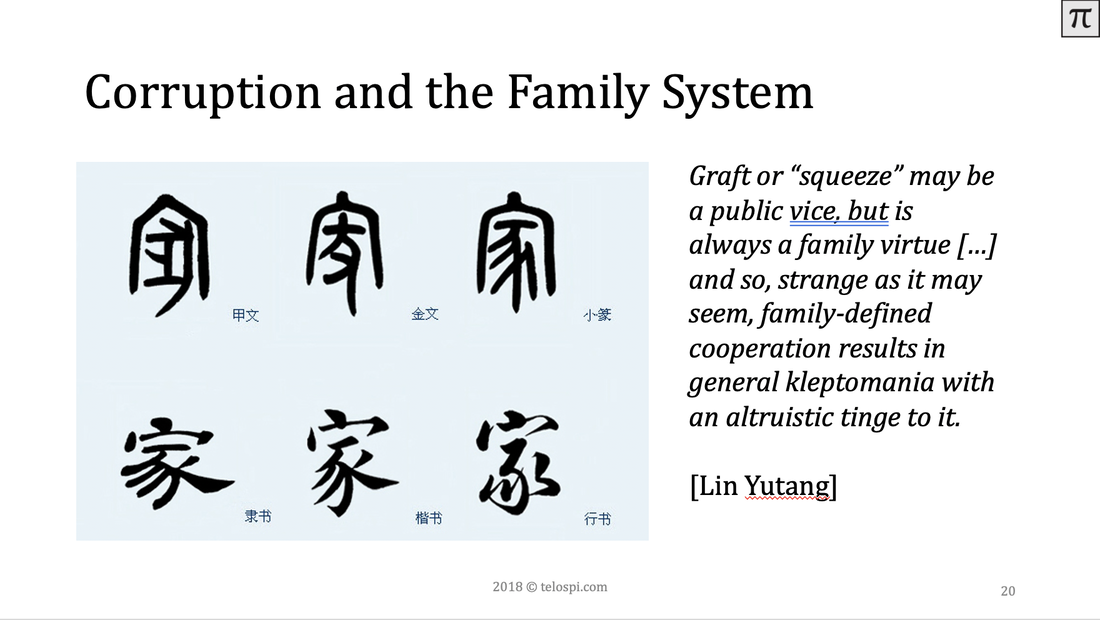

The inseparable connection between corruption and environmental destruction is without question the very top takeaway from this book. Interestingly, many Chinese move to Africa because of too much corruption in their home country: “In their new lands of adoption, Chinese people frequently spoke to me with unaccustomed openness about their hopes for their country and about its problems and failings. I was struck by how Africa, to so many of them, by contrast, seemed remarkably free, and brimming with opportunity unlike home, which they often described as cramped, grudging, and hypercompetitive. For many of them, Africa also seemed relatively lacking in corruption.”

Rather than being corrupt themselves, the Chinese are riding high in Africa because they know how to play corrupt local elites. They buy the ruling class in each and every country whether with scholarships for their children to Chinese elite universities or kickback payments in large public tenders. Effectively, it is the African ruling class, which sells out everything Africa has to offer, mineral wealth, forests, agricultural land, fishing rights, and deprives its people of the opportunity to improve their lots if only modestly. French offers striking examples of the environmental consequences:

- Liberia: “… all of this wealth, all of this good land that they cannot use, all of this forest, these big trees, redwood trees,” he specified, laughing as if in wonderment. “Chinese people would die for this wood. What [the Liberians] need to do is hitch their fate to people who know how to exploit these things, and that will pull this country out of poverty. This region’s forests, when you see them from the air, appear to be as thick on the ground as heads of broccoli. “Do you realize that if you cut down all the trees here there will be no more rain?” I asked him. “Did you know that the countries to the north of Liberia are all arid?”

- Mali: “One could draw many inferences from his remark. One is that Beijing is choosing winners among its state companies at work in Africa. One assumes there are rational policy reasons behind these sorts of decisions, but Chinese businesspeople and senior African officials told me that corruption played a big part. The firms that were most favored by Beijing were paying kickbacks in China for their privileges. Corruption like this is, of course, a mirror of patterns of industrial corruption in China, in much the same way that Chinese labor abuses in Africa reflected the poor labor environment and lack of independent unions back home.”

- Ghana: “Ghanaians complained that Chinese investors and migrants came to the country with one declared purpose, but quickly involved themselves in other pursuits, legal or not so legal. Ghana is Africa’s second largest gold producer, after South Africa, and the stories about illegal mining by Chinese, who cut down forests and despoiled the land with mercury to produce their gold, were legion. Many spoke in broad terms about a Chinese propensity for bribery and corruption, for shoddy goods and for cutting corners. The Chinese-built National Theater, in particular, came up often. It was a gorgeously sensuous, modernist structure with a white roof of sweeping curves. The problem, Ghanaians told me, was that only a few years after being built, it leaked, its tiles were dropping off, and the building seemed to be falling apart.”

- Mozambique: “As it happened, my visit coincided with an extraordinary spate of reports in the local press about Chinese depredations in the north. These ran from an epidemic of major bribery cases involving customs agents to the seizure of illegal fishing boats from Chinese operators. The most spectacular item, though, was an investigative report in the Mozambican newspaper O País, about the impounding of six hundred containers of illegally logged old-growth mahogany and other hardwoods by Chinese operating in the northern forests. Following their initial scoop, journalists were not allowed to inspect the seized wood, and people in the know in Maputo told me that this probably meant that all but a symbolic quantity of the timber was probably quietly sold back to the Chinese loggers, or else auctioned off to other exporters by officials who then pocketed the profits.”

- The China Global South Project: a US based, member financed non profit dedicated to exploring every aspect of China’s engagement with Africa.

- https://www.howardwfrench.com/

- Tom Miller, China’s Asia Dream

- One Belt one Road Initiative

- Niall Ferguson, Empire

- Niall Ferguson, Colossus

- Niall Ferguson, Civilization

- BBC documentary Civilization: Is the West History?

- The Guardian, Black man is washed whiter in China’s racist detergent advert

- Sebastian Heilmann, China’s Political System

- Lin Yutang, My Country and My People

RSS Feed

RSS Feed