People often ask what’s Hong Kong’s appeal after Shanghai’s cosmic rise and the central government’s decisive push to sever the city state from its former special status by setting up SEZ all over mainland, starting with Shenzhen after Deng Xiaoping’s great journey South in 1992. Shanghai is clearly favored by the CCP over Hong Kong as being the present and future financial and commercial pendant to Beijing’s political gravity. I believe though that only those who have scratched China’s surface can ask such a question. When living in Northern or Central mainland for some time, you will understand that Hong Kong is still foreign, even if you just perceive it as the epitome of the Cantonese cultural realm, which encompasses a population the size of all German speakers in Europe.

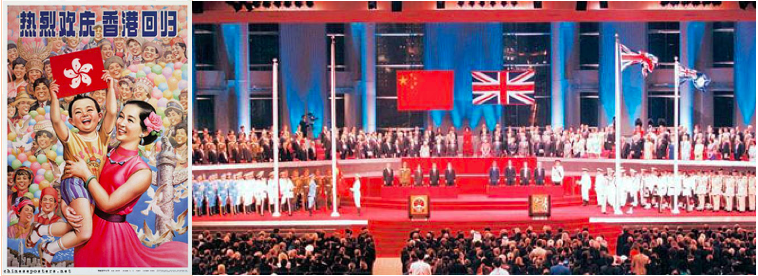

A few years ago I was interested in Hong Kong as the spear head of China’s urbanization, and explored the city’s role as the CCP’s guinea pig to experiment with the future of urban spaces, in particular in regard to the real estate market, environmental protection and the urban middle class. This year, to be precise on July 1, 2017, China celebrates the 20th anniversary of Hong Kong’s return to the mainland political realm, what Chinese like to call in good old Confucian tradition, Hong Kong’s return to the Motherland | 香港回归. A timely occasion to revisit the former colony and spend some time and thought on the meaning of Hong Kong.

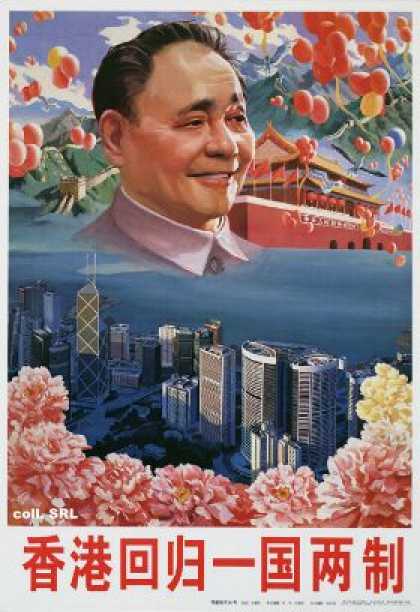

Peter Guy sees the only realistic salvation for his people in quickly merging Hong Kong with China and relinquishing the One Country, Two Systems status. Looking into this concept, one realizes that it is in fact outdated. 1980ies paramount leader Deng Xiaoping proposed it on the basis of China being a socialist and Hong Kong being a capitalist economical and political unit. As of 2017, I am not sure whether there is any difference between the two systems of governance, at least I fail to see it. Both systems are ruled by an alliance of bureaucrats and property tycoons; the average citizen is being exploited; and materialism is prevailing in a social system which the great Lin Yutang described already in 1935 cogently as a form of magnified selfishness, family minded not social minded. In an increasingly global world such an attitude wont help to resolve challenges of supra-regional and even planetary dimension such as environmental degradation or the cybernation of our societies and resulting landslide changes on our labor markets.

Meditating On the Meaning of Hong Kong

The movie Chinese Box was shot during the six months before the return of Hong Kong to China and is generally perceived as a meditation on the meaning of Hong Kong. The plot projects the differences between the societies of mainland China, Hong Kong and Great Britain into the movie’s protagonists, meandering between freedom and captivity, socialism and capitalism, emotional growth and financial gain, fraud and honesty, opportunist liking and consummate love; and Hong Kong born director Wayne Wang succeeds to craft individual characters into a rich portrait of collective mentality dynamics.

John, a mid-aged, British journalist who has been living in Hong Kong for more than 15 years, meanwhile separated from his wife and their children who moved back to England, is desperately in love with Vivian, the partner of Chang, a self-made tycoon. Vivian rejects John’s courtship, and in her hope that Chang will marry her she displays the twisted, incompatible value sets on which her life is based. Chang who seems to have started out his Hong Kong career as sleazy pimp thrived on the acquaintances which Vivian handed over to him as high end prostitute. Both left mainland China in the 80ies for Hong Kong in search of opportunity and abandoned the values of their home society, but now having managed to achieve a certain level of social status and material wealth regress into rigid patterns of cultural conditioning. Chang rejects a marriage with Vivian because of her prostitution past, and Vivian wants nothing more than to confirm to her mother that she has succeeded in Hong Kong by marrying a well off business man. Chang’s love to Vivian is constricted by face | 面子 and mores of purity; Vivian is driven by the Confucian core principle of filial piety | 孝. Both have failed to individuate themselves from the cultural programming of their home societies.

John asks Chang one day upon realizing that Vivian had been a prostitute, “You know why Chinese like blondes? To not be reminded of their wives.” If we believe the Chinese mentality’s most profound connoisseur Lin Yutang, then this joke is based on a cultural misunderstanding: Chinese man most likely don't care. The Chinese regard marriage as a family affair, and when marriage fails they accept concubinage, which at least keeps the family intact as a social unit. The West, in turn, regards marriage as an individual, romantic and sentimental affair, and therefore accepts divorce, which breaks up the social unit. Chinese Box makes me not only once think about what I have occasionally perceived as a distorted moral code when it comes to questions of love. I recall a few Sinica podcast episodes, e.g. host Jeremy Goldkorn ranting that “The Chinese government needs hookers. All politicians are married to some women they don't like, because it was better for their career. The entire government would fall apart if they would ban prostitution.” Or the interview with James Palmer about Business and Fucking in China as well as his excellent article Kept Women. Chinese Box certainly also has some overlap in its narrative with the classic 1934 silent movie The Godess | 神女, which displays the scrupulous extortion single women had to suffer in traditional China, and touches a delicate subject, which must be elaborated somewhere else: the unconscious dynamics of culture in our most intimate relationships.

Shortly after John is diagnosed with terminal leukaemia, Vivian realizes that there is no future with Chang. She decides to break up with him, but when being eventually ready for true love, John rejects her. He who seemed to have understood best of all the differences between China and the West indicated a single sentence “Is our truth any better than their truth?”, is turned by Wayne Wang into a projection wall for a dying democracy and evaporating freedom with only three to six months left to breath. His opening statement “This great big department store is just going to have a change of management” is seemingly falsified by his own death.

Its telling that all three Asian protagonists impersonate mainland Chinese, who have taken different paths in Hong Kong. Chang the path of power and wealth, Jean the path of fraud and opportunism, Vivian being torn between the former two and true love towards John, who represents British virtue amongst a bunch of mostly white trash type of foreigners and dies perplexed over Hong Kong’s multiple identities reflected in his relationship to Vivian. “I used to write about Hong Kong’s future as it has a definite direction, a predictable outcome, but everything in this city has always been changing. Maybe I wasn’t meant to figure you out.”

To the disappointment of many Hong Kongers, Chinese Box is not about them. It is the art work of a Hong Konger, who has left that society long ago; it is his perspective on a society or rather a space, which has provided opportunity for people from different walks of life to distance themselves from their originating societies and experience a sort of freedom they did not have back home; but director Wayne Wang shows that unprejudiced love is the only truth and freedom is not only related to how societies are organized, but also to how much we can make unconscious conditioning conscious and react thereon. He succeeds to create a masterpiece which shows in an emotional narrative that exterior social structures and resulting patterns of behavior have the same weight as our internal structures; and freedom or liberty is thus only to a limited extent related to the system of governance under which we live. In Jung's words: as long as we haven't made the unconscious conscious we call it fate.

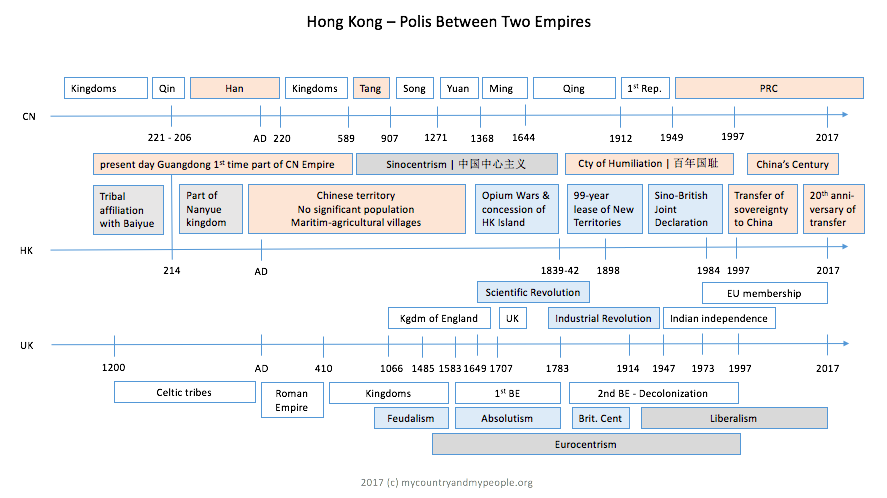

I have meditated myself on the meaning of Hong Kong not only once; its historical and its contemporary significance. The Chinese elite does probably consciously perceive Hong Kong’s concession to Great Britain in 1842 as the starting point of what is generally considered 100 years of humiliation | 百年国耻; the dominating theme of the Chinese collective unconscious. Hong Kong’s return in 1997 on the other hand is widely acknowledged as the end of the British Empire and thus the beginning of a final chapter in the dominating theme of the European collective unconscious: 500 years of imperialism driven by the the scientific and industrial revolution.

Hong Kong’s contemporary appeal to non-Chinese tourists is without question the, albeit superficial, accessibility of Chinese culture through its British heritage; one feels at home although one is clearly not. A mainland resident though feels like being abroad, although he is at least legally not. Hong Kong seems to be neither fish nor meat, but it has been clearly changing in consistence during the last two decades. My favourite indicator for this change is the annual observation of pedestrian behaviour. While people strictly walked on the left when I visited Hong Kong for the first time in the early 2000s, the picture has completely changed as of 2017. The majority of pedestrians walk on the right, but some colonial hardliners insists on walking left and cause quite substantial collision risk. Expect to go out of your way not only once, when strolling on the massive flyover network which connects many of Central’s high rises.

Back in April 2015 I wrote about the Hong Kong – Macao – Zhuhai Bride: A Symbol for Bridging Democracy and Fascism. Like the slow change in the behaviour of pedestrians, this colossal project tells much about the integration of one small entity within a much larger. The meaning of Hong Kong in such a context is one of a polis state being absorbed by a surrounding empire, a handful of sand being lost in a desert, a small rock being washed away by might breakers. And hitherto useful terminology seems to have lost ground. Whether China is fascist, absolutists or even democratic can only be answered by the subjects affected.

The bridge turns before my eyes into a symbol of advantages and disadvantages of democracy and fascism and I wonder how Singapore would have faired in this project would it have been in the place of Hong Kong. Democracy gives people a right to have their say, to stand up for themselves. Authoritarianism excels at executing vast infrastructure projects by streamlining the population, if necessary against its will. Democracy fails to maintain a trajectory for large scale infrastructure projects, because the government must appease the electorate to stay in power for another term. Fascism fails to give important, but from the leadership divergent opinions, a say.

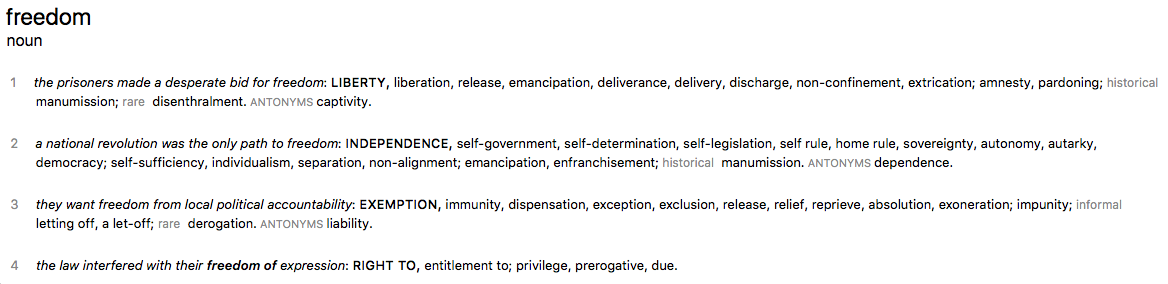

If liberty is defined by free access to media, then I would call Hong Kong free. I was e.g. able to open without any complications a NYT review of Chinese Box when there. Now, being back in Shanghai, I have to use a VPN to read what is not of interest to the mainstream Chinese mind. If liberty is being defined by having access to the world’s largest labour market, then I would agree with Peter Guy that Honkies are not free at all. Remember that the free access to the labour market is one of the four basic liberties of the European Union. From such a POV, Hong Kong is less integrated to China than let’s say Monaco into the EU, and the majority of Hong Kongers would probably laugh at the very high human development index their home nation has been awarded with. If the HDI is about whether people are able to “be” and “do” desirable things in their life, most Honkies would tell you a story of the upper ten thousand and the harsh realities for the bottom seven million. Having to save all your life for a damp and dark 700 square foot apartment, which will set you back between 10 and 15 million HKD in Central and still a substantial amount on outlying islands or the New Territories, will harvest understandable cynicism when others think that you can do desirable things in your life.

Eric Stryson, managing director of the Hong Kong based Global Institute for Tomorrow wrote in a recent announcement for a fall 2017 conference that Hong Kong has a housing affordability crisis. Solutions to date have been crowded out by convoluted arguments and intractable positions. The city’s housing — the world’s most unaffordable — is making headlines for all the wrong reasons, such as Bloomberg’s report that an apartment smaller than a Tesla Model X sold for US$500,000. A recent opinion in The South China Morning Post argued that Hong Kong’s housing quality represents a totally unacceptable state of affairs in one of the world’s wealthiest cities, and the most significant drag on the city’s overall quality of life.

Ever heard of Georgism? It's an economic philosophy originating in the 19th century, which postulates that economic value derived from land (including natural resources and natural opportunities) should belong equally to all members of society. Its founding father, American political economist Henry George, argued that governments should be funded by a tax on land rent rather than taxes on labor. But both the Hong Kong and the mainland Chinese government revenues are based though on a power structure which rests on two pillars: real estate tycoons and the government, using land in good old feudalist tradition.

If liberty were defined by being able to purchase goods and services of one’s desire, a definition which held certainly some truth in the socialist nations of Eastern Germany or the UdSSR – you will certainly recall that Levis won the cold war - both Hong Kong and China have lifted their citizens – real estate excluded - into freedom’s Olympus. It would be worth discussing whether the form of governance or technological progress was the main catalyzer for that progress, but if man searches more and more for meaning beyond materialistic satisfaction, affluent consumer societies loose their appeal, no matter how they got there and whether they rather resemble Orwell’s 1984 or Huxley’s Brave New World. I have lost my preference for modern democracies over totalitarian regimes. In case of Hong Kong and China they are same same, but different.

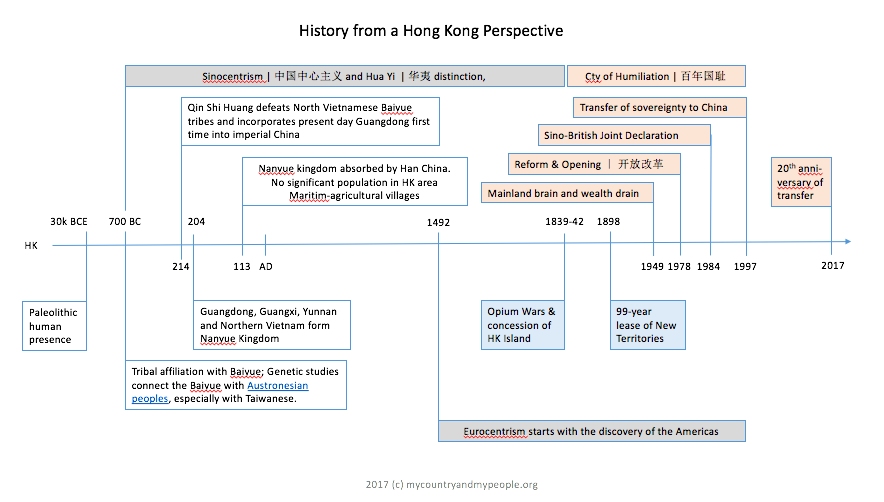

Winston Churchill once said that the further we look into the past the better we can understand the future. I therefore want to venture into China’s past to understand societal changes in contemporary Hong Kong and probably the future world at large. The area of Hong Kong was for most of recorded BC history part of tribal affiliations which encompassed the area of northern Vietnam and Southern China. The Baiyue or Hundred Yue were various partly or un-Sinicized peoples who were considered as barbarians who lived in primitive conditions and lacked technology as bows, arrows and chariots. During the Warring States period, the word "Yue" referred to the State of Yue in Zhejiang - nowadays dubbed as China’s Switzerland - indicating that Yue tribes spanned from an early Chinese perspective the entire area south of the Yangtze. The later kingdoms of Minyue in Fujian and Nanyue in Guangdong are both considered Yue states. Genetic studies connect the Baiyue with Austronesian peoples, especially with Taiwanese. The Yue were assimilated or displaced as Chinese civilization expanded into southern China in the first half of the first millennium AD, but considerable differences in general physiognomy between Northern and Southern Chinese in particular, can still be traced back to this period.

Qin Shi Huang, the Chinese Alexander the Great, brought present day Guangdong 214 BC under his rule and thus first time directly under Chinese cultural influence, albeit only for a few years, because in 204 BC the Kingdom of Nanyue established itself after the collapse of the Qin Empire in the area of Guangdong, Guangxi, Yunnan and Northern Vietnam, once again confirming the then prevailing cultural affinity of the region to South East Asia. Han Dynasty rulers perceived Nanyue as a vassal state and formally annexed the area in 112 BC to integrate it permanently into the Empire. The Nanyue period is considered to have contributed greatly to the sinification of the Baiyue peoples, since the ruling elite hailed from Northern Chinese heart lands.

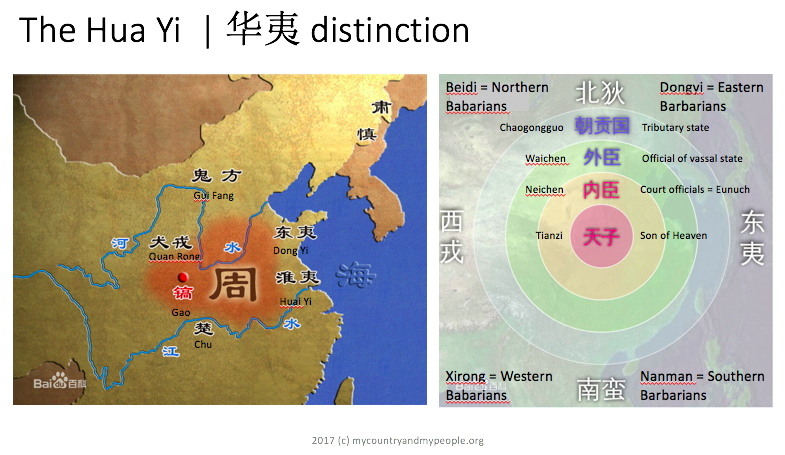

It is widely agreed amongst historians that the distinction between “sinified” and thus from a Chinese perspective culturally superior peoples and all others, the so-called Hua-Yi dichotomy | 华夏蛮夷emerged already during the Western Zhou Dynasty (1041-771 BC) and was reinforced during the Spring and Autumn Period (771-476 BC) when the Western Zhou Dynasty was breaking apart and unity amongst the increasingly warring states was sought by establishing a unifying cultural code, which set ancient Chinese apart from their surroundings. It ultimately led to the now still prevalent concept of sinocentrism | 中国中心主义, which was refined during the Han Dynasty into a division of humankind between Huaxia | 华夏 and Manyi | 蛮夷, a civilized society that was distinct and stood in contrast to what was perceived as the barbaric peoples around them.

The barbarians were seen as the far extreme opposite of the emperor or Son of Heaven | 天子, who was divinely appointed and emanated universal and well-defined principles of order. His spheres of influence were clearly classified according to physical proximity and as such exposure to his culture, into court officials, officials at vassal courts, tributary courts and their respective subjects, and finally barbarians, who were not yet under his heavenly mandate. Later dynasties, in particular the Ming who moved the capital in the early 15th century to Beijing and had there the Temple of Heaven | 天坛erected, continued to apply this essentially social and strongly hierarchical structure of the emperor and his court being the center of the known world, culturally superior to any other form of human life. Only if one tries to understand this more than two millennia long self-perception of the Chinese elite, one can phantom the emotional dimension of the what the British kicked off in 1839 with the Opium Wars and what is known by the Chinese as Century of Humiliation | 百年国耻.

There were similar distinctions made e.g. in the Hellenistic worldview, which differentiated between Greeks and barbarians, but none of these concepts of cultural racism prevailed into modernity. Today, I believe its important to understand the historical roots of sinocentrism, because of three reasons. Firstly, because sinocentrism paired with 大同|Great Unity, a Chinese concept referring to a utopian vision of the world in which everyone and everything is at peace, effectively creates an agenda which is similar to Islam, i.e. the global spread of a set of values from a center of gravity, which is Beijing in the former and Mekka in the latter. Secondly, because Chinese language lends itself as the ideal vehicle to establish a schism between the Middle Kingdom and the barbarians. Thirdly, because China is probably the only political entity which realistically could surpass the 20th century influence of the US. All indicators point towards a shift from a pax americana to a pax sinica.

The Hua-Yi dichotomy and any other worldview which separates humankind in two groups results in growth as long as it remains open in order to absorb other peoples as it was e.g. the case during Tang China, which despite prevailing sinocentrism is considered to represent the peak of Chinese culture; but it results in stagnation or even decline if doors are shut and segregation measures are taken, e.g. under Ming China or Edo Japan. Modern China could be perceived since 1989 as a country which despite global trade gradually closes itself - in good old Japanese sakoku style – off from ROW. Jiang Zemin introduced the patriotic education in the 90s, Hu Jintao technonationalism in the 2000s, and Xi Jinping oversees the implementation of cyberleninism since the 2010s which includes turning the internet in China into an intranet – separated from the Western world.

The medieval diplomat Niccolo Macchiaveli who was something like an Italian version of Confucius, providing his services of government advisory to different courts of his time, and whose ideas could be understood as the foundation of enlightened absolutism, wrote in The Prince that men are driven by two impulses, love and fear … it is much safer to be feared than loved. The similarity between Jesus Christ, the Son of God and the Son of Heaven, a supreme universal emperor who rules tianxia comprising "all under heaven" which translates from the ancient Chinese into English as the "ruler of the whole universe" or the "ruler of the whole world” is striking. One spreads his gospel through love, the other rather through fear, but both claim to be the incarnations of heavenly values. Chinese monarchs were referred to as a demigod or deity and most modern rulers like Yuan Shikai, Jiang Jieshi or Mao Zedong did their best to emulate their predecessors, with the latter definitely succeeding therein. China’s new helmsman Xi Jinping is well on track to reestablish the integral bond between government power and tradition, turning the wheel of time back into an era when neither China nor the West were secular, a Pope acted as statesman and an emperor was the son of God.

A City State Between Two Empires

The American philosopher Ken Wilber wrote that it is the nature of the [evolution’s] leading edge stage that its values, although they are only directly embraced by the stage itself, nonetheless tend to permeate or seep through the culture at large. Hong Kong was both strategic part of the British Empire, the largest empire in human history, which 1913 held sway over 412 million people, 23% of the then world population, and by 1920, it covered 35,5 mio km2 or 24% of the Earth's total land area. Now it is part of the modern Chinese Empire, which calls more than 1.3 billion people its subjects, i.e. roughly 17% of the world population, which constitutes since 2013 the world’s largest economy in PPP and soon also in GDP. The polis is therefore the playground of competing values of two imperialistic success stories, which can serve well to elaborate on the ingredients for civilizations and their progress.

Considering that Hong Kong’s population, as a matter of fact the global population, was insignificant until the begin of the industrial revolution and in particular in regard to the subject at hand until the Opium Wars 1839 – 1842, its safe to say, that Chinese values have played only an indirect role in the rise of the city state. Hong Kong’s population grew between 1841 from a few thousand settlers to 6.5 million in 1997, but has since then only increased to 7.3 million. Something about Hong Kong must have certainly had until 1997 an appeal to mainland Chinese; and if it was only the simple material fact that the tiny city state was then worth 1/3 of mainland’s entire economy.

Let’s try therefore a comparison between Orient and Occident to answer where Hong Kong’s attraction lied in. Historian Niall Ferguson argued in his 2011 oeuvre Civilization – The West and the Rest, that six novel complexes of institutions and associated ideas and behaviors distinguished the West from the rest and were causal for the Eurasian world dominance for the last 500 years. These novel complexes are competition, science, property rights, medicine, consumer society and work ethic; and Ferguson calls them killer apps, because they helped European powers to outperform all other cultural entities on this planet roughly until the turn of the millennium or respectively until the return of Hong Kong to China.

I would like to argue instead that these six killer apps are merely consequences of a much deeper change in values (or growth apps) which Europe did undergo since the Renaissance, the rebirth of classical antiquity, at first in Italy and then spreading across Western Europe in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries, and again resurging during various neo-classical revivals in the 18th and 19th centuries. Europe evolved then because it studied and applied the ideas and values, which helped the Greek and Roman civilizations to flourish from roughly 800 BC until 500 AD before the continent plunged into the hitherto labelled dark middle ages.

Renaissance humanism took center stage and was a response to the utilitarian approach and what came to be depicted as the "narrow pedantry" associated with medieval scholasticism, a school of thought which reminds me strikingly of the Chinese tradition to study the Confucian classics. The Greco-Roman cultural foundation has been immensely influential on the language, politics, educational systems, philosophy, science, art, and architecture of the modern (Western) world and it is therefore widely considered the cradle of European and Western civilization at large, thus being the main reason why Europe and its colonial offspring, the Americas, share most of their values. Trying to identify the part of classical antiquity which had most impact on how the Western world defines itself, we must arrive at humanism, a school of thought which sought to create a citizenry able to speak and write with eloquence and clarity and thus being capable of engaging in the civic life of their communities and persuading others to virtuous and prudent actions. In short, humanism promoted personal growth, albeit then mostly restricted to male members of the respective societies.

Humanism was the growth app which made ancient Greece and the Roman Empire flourish; humanism, the competition between Italian city states, and Machiavelli’s recommendation to ruling nobles to be unjust or even cruel in order to achieve noble ends, sparked the scientific revolution, and the scientific revolution in turn the era of enlightenment, culminating in enlightened absolutism, which is the Western pendant to the Chinese concept of an emperor being the son of heaven | 天子and ruling all under heaven | 天下 under a divine mandate. Liberal humanism was restricted in the West until the 19th century by enlightened monarchs, but the balance tipped in favor of individualism, whether this be dictatorship or the appearance of narcissistic consumer societies, and ultimately led into the chaos of the 20th century.

The Chinese antiquity produced two schools of thought which can be understood as Oriental pendant to humanism and absolutism. Taoism emphasizes like humanism the freedom of the individual and teaches a natural suspicion against any form of social organization. Confucius understood the ruler like Machiavelli as the principal subject of the state, which has to compromise short term individual freedom in favor of long term goals. Confucius’ concept of a society ruled by gentlemen | 君子 reflects that his political science was never to be understood as totalitarian or strictly hierarchical; he propagated an ideal society ruled by an enlightened monarch, who embodies the virtue of benevolence and whose acts are in accordance with the rites of rightfulness. 君子喻于义小人喻于利 | The gentleman understands what is moral; the small man understands what is profitable.

The English Republic was short lived. Oliver Cromwell establishes himself as de-facto king - like Napoleon after the French Revolution – in 1653, with Charles II returning to throne in 1660 with seriously reduced power, making England next to the Netherlands one of the freest places in the world. The Bill of Rights, based on thinking of John Locke, is passed in 1689 establishing that the sovereign can not suspend laws passed by parliament nor levy taxes without parliamentary consent. The still lasting era of parliamentary monarchy begins in England, while other European nations choose to prosper as parliamentary republics. Humanism led in Europe to a gradual increase of personal freedom and supported individual growth; whereas China was stuck for 2.5 millennia in a divinely sanctioned stasis.

The British chemist Joseph Needham who spent the better part of his life researching the technological developments in historical China argued that bureaucratic futilism did ultimately lead to the decline of the Ming and the collapse of the Qing dynasties. I believe that bureaucratic futilism was rather a symptom of a decaying civilization. Confucius would have explained the reason for China’s decline in the 16th century and ultimately its colonization by imperial powers in the 19th century with a lost focus on what really matters. Instead of morals, Chinese rulers built their future on profit only; and sometimes not even that considering the debt of the late Qing court. Despite a stable bureaucracy, they lost their divine mandate – then only over generations - by not living as an example for their subjects. The Chinese elite is said to fear grass root uprisings like the Boxer Rebellion or the Falun Gong Sect, but actually they should fear their own moral decomposition.

Ian Johnson writes in The Souls of China, that president Xi has made since 2011 the rectification of national morals his top priority, which indicates that he either understands what matters or some smart advisor has told him to turn to faith as the last bastion against the socially destructive forces unleashed by the industrial revolution. We don’t know yet if China’s helmsman supports individual growth, but concluding from the China Dream or One Road One Belt campaign, he certainly has the nation’s development on his agenda. Does this make him into an enlightened monarch or an authoritarian ruler? Does this make him into a Frederik the Great, one of the most distinctive monarchs of European enlightened absolutism, who considered himself the first servant of the state, or Napoleon Bonaparte, one of the greatest generals in human history, who was most likely motivated by an inferiority complex?

I guess that the answer depends on the subject asked. Mainland Chinese will perceive their president’s measures against corruption and his support for traditional religion as a step into the right direction, because they aim at establishing a just and peaceful society. Honkies, who have been used during the last decades to more personal freedom than their mainland cousins, might see Lord Vader descending upon their turf. They might forget though that Hong Kong was not all that liberal under English colonialism, which made it difficult for natives to rise through the ranks. They might also forget, as one fellow traveler told me recently, that increased personal freedom through liberal humanism was only one of three ingredients for Hong Kong’s economic rise. The other two were a massive mainland brain drain before and after 1949 and the colony‘s mediator position between China and the West in the early 80s. Thousands of well educated and wealthy - mostly Shanghainese - left mainland when the Communists got to power and moved to Hong Kong or Taiwan, inflicting on the country a similar brain drain like the Nazis did on Germany before WWII. The rise of Hong Kong is therefore a story which bears some resemblance with the rise of the US relying heavily on being an attraction for human talent. Hong Kong’s unique geopolitical position during the early years of the economic reform era | 开放改革, when China started to open up to the West, but was not yet able to directly interact its customers, established itself as the Asian if not global trading power house, a Seville of modernity.

After all, it seems as if Wayne Wang asked the right question in Chinese Box: “Is our truth any better than their truth?” The socio-psychological truth of how to organize societies must be somewhere in between total exterior control and total interior freedom. The homo socialis is per definitionem a networked species which can define liberty only in relation to others. Liberalism and absolutism - and the same is true for Taoism and Confucianism - are therefore like black and white two extremes which can’t work alone. They need each other to make sense. What is true on this political level of dealing with societies is therefore also true on the systemic level of families, when real parents deal with their children and struggle between authoritarian Confucian control (only I know what is good for you) or laissez fair liberalism (you have to know yourself what is good for you). The state takes the role of a parent surrogate influencing its subjects; and like a parent he either supports the personal growth of his offspring or he stifles the same.

I increasingly tend to see in Xi Jinping an enlightened monarch, because similar to the 18th century enlightenment models Prussia and Scotland did China experience the scientific and industrial revolutions during the last few decades and engages currently in a renaissance of Chinese antiquity. Thus, Hong Kong could not have hoped for any better. Suffering from blatant individualism which created the before mentioned housing crisis and indulging in the world’s sickest consumerism - with the world’s largest casino next door - China’s modern son of heaven might well be, what that society needs. As the sinocentristic circles once again expand, we must though wonder whether Beijing’s value broadcasting on channels 16+1 (China and CEE Countries Cooperation Organization), SCO (Asian Countries Cooperation Organization), One Belt One Road (all roads lead to Beijing initiative), etc. is nevertheless cacophony to the rest of the world. This is not a critique but rather a statement; because it would be asked too much of a nationalist 19th century leadership, which deals now with what other industrialized nations dealt 200 years ago, to find in addition answers to questions of 21st century global dimension.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed