And so it turned out to be. I was glad I had done my homework. Things got quite often out of control and I had to let go not only once by skipping a temple afternoon visit in favor of an extended lunch followed by ice cream, but it was good to have my plan as a platform from which we could navigate from – even though we ended now and then in some Zen abyss. The weather did contribute: It was awfully hot this summer; for any kind of journey, but especially for a family holiday with our two restless children. It was in particular hot in Nara, where I understood why Japanese people sometimes have a passionate affinity for the boiling regions of India. Our children were thrilled nevertheless and nervously anticipated the promised deer freely roaming the park. [Daughter excitedly pointing at a map next to the train station ‘There is the deer park!’ Father drenched in sweat and hauling the second born hopefully lifting his head ‘They have a beer park?’]

In Nara we also ran into a long haired, probably 55-year-old dude watering his wild, not at all Zen like front yard. Overhearing us speaking German he asked us where we were heading to. It turned out that he spent several years in the German province Hessen. Later that evening we met him and his German wife, who had been living in Japan for 21 years, to chat some more. On parting I asked the couple jokingly if they ever perceived themselves as the axis of evil. He pondered for a moment and replied with a smirk that Adolf Hitler was Austrian after all.

Most countries I travel to for the first time, I try to understand upfront through one or two recommended books. The Financial Times staff has already once been a substantial aid in doing so: when I travelled to India for business purposes in 2008, I read the then recently published title In Spite of the Gods by FT’s long time India correspondent Edward Luce. That read was of such enlightening impact that I didn’t hesitate one second, when I read somewhere that a long time FT correspondent to Japan, named David Pilling, published 2015 a book titled Bending Adversity. I bought, read and did enjoy. I am not an economist, but there is something I truly enjoy from a rational point of view, when journalists with a profound economic background report on a country. I read them as representatives of the humanities at their most rational and best, because they ideally combine their insights of sociological and collective psychological dynamics with the recorded data of the financial world. It was the historian Harari who wrote in his epochal oeuvre Sapiens that the earliest records of written human activity are not poems or political treaties nor scientific papers, but simple accounting notes. There has to be something of intrinsic relevance to such information, which can’t be dismissed.

Pilling had been on my reading list for more than a year, but working my way through Lonely Planet’s Japan guidebook, I encountered in the movie and book recommendation section A Different Kind of Luxury by Andy Couturier. The subtitle Japanese Lessons in Simple Living and Inner Abundance got me instantly interested. I bought, enjoyed, but till now I have finished only six out of eleven “case studies” Couturier has collected. As the author suggests himself, I slowed down reading, because it indeed takes some time to digest each one of the featured characters and their abundant philosophical mindset and practical life perspectives. I reckon that this travel essay is therefore somehow a personal review of both mentioned titles intertwined with my own take on Nippon.

What did I know of Japan before we went there? To be honest: almost nothing. But then again, screening my memory, there are books, movies and many stereotypes that are worthwhile to spend some minutes on. I recall first of all reading Eugen Herrigel’s Zen in the Art of Archery, one of my all time top ten reads. It’s the 80 something pages account of a German philosophy professor who spends with his wife a few years before WWII teaching in Tokyo and tries to understand Zen by practicing archery; his wife by the practice of ikebana. I have a very fond memory of this book, because of its brevity and prosaic depth, and I believe it has formed my picture of Japan or what can be encountered in Japan like nowhere else.

I was never able to put this potential encounter in words, but Pilling quotes in Bending Adversity Japan Through the Looking Glass by Cambridge anthropology professor Alan Macfarlane, who managed to to so: Whereas other modern societies had gone through a profound separation of the spiritual from the everyday, no such division ever took place in Japan. It never underwent what German philosopher Karl Jaspers called the ‘Axial Age’, a separation creating a dynamic tension between the world of matter and another world of spirit. Japan had no heaven or hell against which to benchmark its worldly actions. ‘Japan rejected the philosophical idea of another separate world of the ideal and the good, a world of spirit separate from man and nature, against which we judge our actions and direct our attempts at salvation.’ In my own words I would say that Japan is probably the most monistic and industrialized society which can be encountered on this planet, and all the uniqueness which might be perceived from the one or other perspective is a consequence of this condition. The Japanese have a term proper for their uniqueness: Nihonjinron. Pilling explains Nihonjinron as the study of what it means to be Japanese. An exercise in exceptionalism, it underpins a strong Japanese sense of national identity but is often taken to fetishistic extremes. Nihonjinron could be the Japanese version of what China claimed for hundreds of year for itself: cultural superiority.

There are also a few movies which contributed to the picture I had of Japan. Lost in Translation with Bill Murray showed me a Japan which I knew very well from China: the foreigner feeling like a spider in an ant hammock, the tall white guy lost in a sea of yellow dwarfs, estranged by pastime activities like KTV and Pachinko saloons. Nokan, a pretty recent movie about a professional cellist who turns undertaker, poetically describes the art of funeral arrangement and Suzako, a movie from the late 90ies shows the decay of a village community as the death of an organism. And of course Spirited Away, to pick only one movie from the many produced by Hayao Miyazaki, about a girl who slides into a Buddhist inspired ghost world. All these movies conveyed to me this holistic and somehow mystical picture I have at the back of my head of Japan and only by reading about Karl Jasper’s concept of the Axial Age I can make sense of this perception.

The concept of Japan not having undergone a separation between the spiritual and the profane alone makes it an interesting subject of study, but there are other qualities to Japan like its demographics, its degree of industrialization and its resulting macro economics, which are interesting to ponder on. Japan is in all these aspects a sort of frontrunner for other countries, and foreigners seem to be mostly drawn to Japan because they want to derive conclusions for the future of their own societies or humanity per se. I confess that my mind was loaded with many such thoughts throughout our journey across Japan. But what really stuck with me is this feeling that heaven and hell are both part of our profane lives; and that all Japanese creatures are enormous, except its people. We were astonished by the size of Japanese bugs and slugs, as we were stunned by its Lilliputian people. Women are petite and most men rather boyish compared to their Western counterparts. Being slim myself, I am not surprised anymore that I don’t find my size at Uniqlo stores.

Children of a Common Mother

Japan is surprisingly similar to China; I was amazed to actually see many more similarities than differences and realized that there has indeed been inflicted some brain washing upon me through my experiences in China. Chinese and Japanese share a large part of their culture, and I was reminded of the relationship between Great Britain and the US. There is a large memorial at the border between Washington State and British Columbia, which reads to border crossing motorists as such: Children of a common mother. Great Britain is to the US and Canada probably in a similar relationship as China to Japan and Korea. So, 2001 memories of my Chinese students being infuriated by nationalist propaganda movies about the atrocities committed by the Japanese army in 1937 in Nanjing faded over witnessing delighted Chinese tourists taking photographs of Tang dynasty temples in Kyoto and recognizing their own culture in a country which they have been ordained to hate.

Japan, the Industrial Front Runner

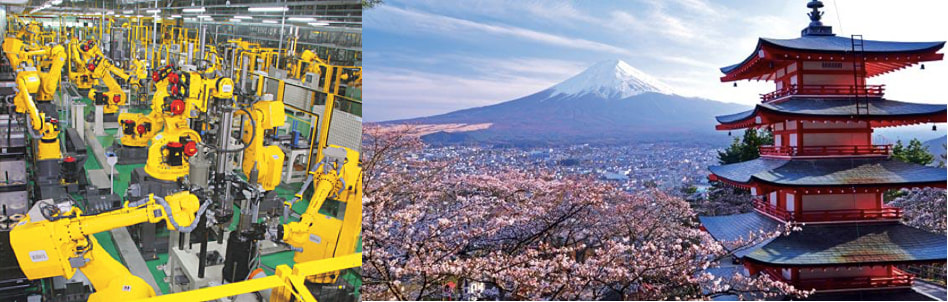

My professional career has led me deep into the world of robotics during the last few years and I was therefore exposed to a substantial bit of Japan’s industrial might. Four out of the big six global robot manufacturers[1] are Japanese and some minor manufacturers with quite famous names[2] usher substantial global activity, in particular in China, where my Japanese business partners told me on various occasions that the battle for the robot market will be decided. Japan though, is currently as a society the most industrialized and commercialized nation on the planet, and I saw the impact of this development everywhere, whether it be the world’s largest industrial robots manufacturing site at Fanuc headquarters, an automated, waiter free restaurant or the abundance of small Lawson and Family Mart convenient stores, which have destroyed any different form of groceries’ trade almost in it’s entirety.

Japan’s struggle with industrialization epitomizes in my eyes at Fanuc. The company was founded in 1958 by the engineer Dr. Seiuemon Inaba, about a decade before the third industrial revolution is commonly assumed to have started and focuses its business activity exactly on the two core technologies of that revolution: robotics and IT. Fanuc is short for Fuji Automated Numerical Control, indicating all you need to know. Located of all locations you can think of in the Mount Fuji National Park at the very foot of Japan’s holiest mountain, Fanuc started out with manufacturing control systems as part of the conglomerate Fujitsu, now the world’s 4th largest IT service provider. After its spin out, the company was at the very center of Japan’s economic miracle enabling many well-known consumer brands like Panasonic or Toshiba to manufacture with ever decreasing human employment at ever increasing speed and efficiency. The trademark yellow industrial robots are currently considered to be the industry’s state of the art technology. Fanuc’s consistent high quality products are said to be the consequence of operating only one manufacturing plant which is subject to a most rigid supply chain control and quality inspection. I personally consider two aspects about Fanuc worthwhile mentioning: it generates a revenue of more than 6 billion USD with only a bit more than 5000 employees [that’s a whooping revenue/employee ratio] and is literally an autonomous manufacturing unit, i.e. using its own product to manufacture the products its sells. The entire facility is staffed out with yellow Fanuc robots picking, placing, welding and assembling the robots which are shipped to Fanuc’s global sales network, providing the company first hand user feedback in its own premises. I know a few manufacturing and research executives who would sacrifice a finger for having such short feedback loops to improve their products. But above all, I am in awe and terror about the measure of power which rests in the hands and wallets of the Inaba family and Fanuc’s extended clan of shareholders. A faint taste of what is sure to come with the merger of robotics technology and artificial intelligence.

But what are the social implications of such a machinery might? A country which enjoys such a high degree of industrialization is in the grip of Belphegor, the demon of sloth and continuously ranks amongst the top 3 countries in the WHO suicide statistics. Japanese are naturally industrious people being conditioned by Confucian virtues, but a society which deprives man of being engaged in manual work or work in general, makes it difficult to remain productive and give life a purpose but consumption. A stroll through the icon department store Loft reveals a sheer endless choice of useless products, and one might ask like myself “What for?” or “Who buys that crap?” Supermarkets shock despite the cleanliness of Japanese cities with compared to Europe useless and neurotic extra packaging; every biscuit, every single candy wrapped in wasteful plastic.

Japan’s industrial countermovement is though vibrant and visible through small craft shops, which mushroom everywhere. Bike builders, shoe makers, flower arrangers and artisan carpenters are a proof that many young Japanese have turned their attention to craftsmanship despite the high degree of automation. I found this movement quite refreshing and was amazed by the quality of workshops seen. Andy Couturier describes in his book The Abundance of Less, how a few Japanese, who reject the industrialization of their society, have chosen to live in the mountainous countryside, where they do not partake in the consumer society. The conscious choice to be productive despite a collective consumptive conditioning is what I find most remarkable about his case studies. But not everyone is built to be deprived of the amenities which city infrastructure provides. Its therefore equally promising that there are seemingly more and more Japanese who try to combine an urban lifestyle with craftsmanship and hopefully reduced consumerism.

[1] Fanuc, Panasonic, Yaskawa, OTC. ABB and Kuka are the only non Japanese left in this highly competitive global market.

[2] Kawasaki, Epson and Naichi to name just a few

It seems to me that Japanese are after all incremental innovators who are at their best when they improve existing basic innovations. We saw so many examples in the streets like umbrella holders on bikes or ultra comfy e-bikes with front and back children seats; not believing that these small improvements amongst many others have not travelled yet to Europe or China. If I had to set up my own research team, I would try to get a complimentary mix of Western type researchers who have the spirit of pathbreakers and Eastern type engineers who are capable of paying attention to detail, improving any product they set their eyes on. These are stereotypes, I know, but the Japanese strength of incremental innovation is in my opinion also a reason for Japan’s current disorientation. All Western innovation seems to have been absorbed and refined. Japan has thus turned into the world’s second largest economy and for another good while it will be the world’s number three. But a society, so advanced and wealthy, which has turned into an Asian Switzerland as Pilling puts it, needs to move its focus towards pathbreaking fundamental innovation, of technological, economic and social nature; and above all, I believe, that the Japanese on an individual level as well as on a collective one, need to redefine their ikigai, i.e. their purpose, which is in my opinion not anymore solely related to the wellbeing of its own society, but Japanese, Japanese enterprises and the Japanese nation need to ask themselves, what can be contributed to the global community. There is much that can be learned from Japan; there is much what a sakoku nation can learn from the ROW; this is also true for aspiring sakoku nations like China.

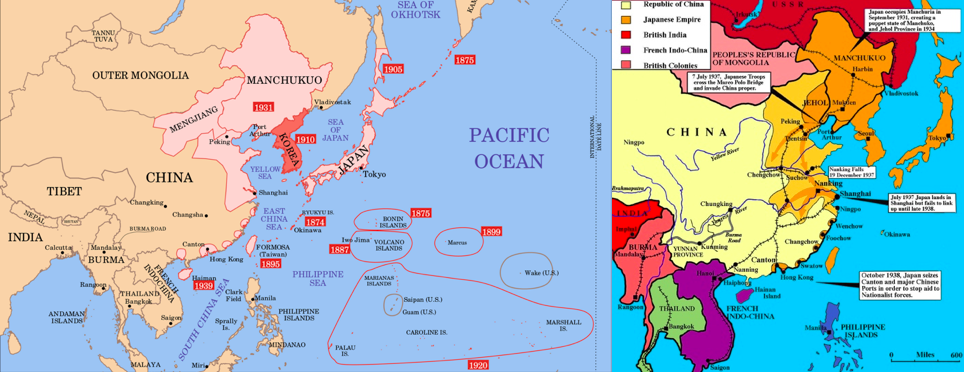

Before traveling to Japan this summer, we made a detour to Heilongjiang province, where my wife hails from. I joked that we first visit the former Japanese colony Manchukuo before we actually go to Japan. That goes not down well with Dongbei folks, I tell you. Upon taking the train from Daqing to Harbin, passing through the wide and fertile plains covered with forests of oil rigs I realized how wealthy this region is, respectively was, in natural resources. Fossil fuel, timber, fertile soil, water in abundance and lots and lots of open topographically plain and arable land. My wife quite plainly replied that the Japanese were not stupid, they took not only the easiest accessible but also one of the richest part of China.

Interestingly, she did also criticize the industry of her Dongbei countrymen, ‘who have made nothing out of that natural wealth, because they are lazy compared to Southern Chinese.’ The social psychologist Thomas Talhelm explains the difference between Northern and Southern Chinese cogently with the Rice Theory of Culture: the labor intensity of rice forced agricultural societies to collaborate closely and be more industrious than societies which grow wheat. It kind of seems obvious that patterns of behavior are established by the crops Semitic societies predominantly cultivate over many generations. My wife’s family are therefore a bunch of wheat idlers; and the rice theory of culture is a lucid example of how social conditioning appears to be genetic inheritance, how constructivism and determinism melt, no matter which side of the argument we choose.

Sir Ken Robinson explains cogently that the industrial education system, which conceives children as assembly line products to be molded after a government’s strategic goals, has an early expiry date, because it ignores the potential of tapping into the individuality of each student. But as we know all to well, empowering the individual is often perceived as weakening the ruling elite. It is understandable that China is in its social development not yet there, where societies which have already experienced 250 years of industrial revolution, hover. But we all know that things move on a completely different time track in the Middle Kingdom and many Chinese parents are fully aware that the domestic education model does not serve the interest of their offspring. Hundreds if not thousands of hybrid curricula have mushroomed over the last decade enabling Chinese kids to study abroad while attending secondary education at home. An October 2016 internal document of the Shanghai Education Bureau discusses plans of banning these hybrid curricula to reestablish the governments education monopoly for compulsory schooling.

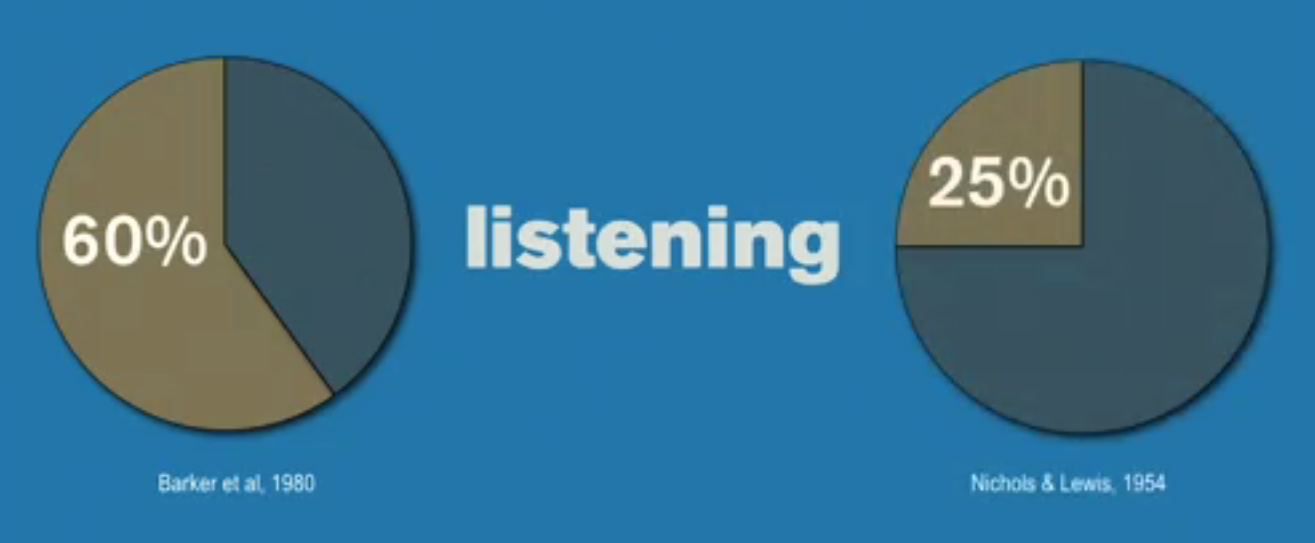

I wonder what the Dalai Lama would tell the Chinese, if he were allowed to visit the country. He most likely wouldn’t recommend to learn English, because the Chinese speak much better English than the Japanese. But he would probably emphasize the competence of listening. A competence which our species looses in general due to our gradual decent into the virtual world. A loss which is aggravated for the individual by national sakoku policies. A global and connected world needs good listeners and international team players; not scientists and engineers whose employers find suffice in their foreign patent database reading skills.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed