What did he exactly mean by that? Shen described American foreign policy as being outspoken and self-inflated. Trump’s Make America Great Again campaign is in his eyes nothing more than flexing muscles during the presidential campaign. He considers Trump to be a business man in the first place and that’s what he thinks is the preferable partner for Beijing. Clinton might fuss about human rights or other democratic concepts. Beijing is not interested in that. Rather have some self-inflated strong man rattle the sabers, but pragmatically retreat from the costly military Asia Pacific engagement, than a Gutmensch politician receive the Dalai Lama and continue to support intimidated neighbor nations in the South Chinese sea with destroyers and air craft carriers. In other words: pragmatic and value free capitalism. That’s what leading Chinese IR academics hope for the future of Sino-American relations. I am strangely reminded of Chamberlain’s appeasement politics before WWII. Don’t get into the way of a rising power as long as we can safeguard in our home turf existing power structures.

On a meta level, I found it interesting that one could read between Shen’s lines the same imperialistic-elitist mindset, which is so common amongst Chinese (as well as American and Russian) males who are interested in power politics. The Chinese collective psyche, at least in such circles, is dominated by 150 years of humiliation and China’s natural right to regain supremacy. I found it particular alarming though that even distinguished IR experts like Shen, who has spent considerable time abroad, don’t even share a thought on post-national collaborative scenarios. Nationalist-materialist blueprints for the future of this planet will not resolve existing challenges. They will, if anything, create more trouble.

Speaking about trouble: The FT published this weekend a substantial article on the South China Sea titled Building Up Trouble. It elaborated on the recent The Hague International Court of Justice ruling over a case brought forward by the Philippines against China. I really do understand China’s need to protect itself. I do also give my elitist Chinese friends the credits to choose realism over constructivism. But in the end, what I really want isn’t IR theorists categorizing international politics. I want a pragmatic and solution oriented approach, which puts off my thoughts that raising my two children in Shanghai might be a bad idea in the years to come.

Top dog China watcher and Sinicism newsletter author Bill Bishop left China last summer and did fuel such thoughts once more in his final Sinica podcast appearance. He explains his decision to leave China straightforward: it’s not about who will be the next president. Both Clinton and Trump will have to deal with a Congress which has changed its attitude towards China. The years of engagement and the false believes of making China more like the US are over. The reality has settled in: China will never be like the US or the West respectively. Bishop therefore thinks that the US Congress will be more likely to support military action against China.

On a rather philosophical note I want to share here my own view by describing the difference between realism and constructivism in international relations and how both are doomed to fail. Wasn’t it always philosophy which showed the path forward, when man engrossed with himself and the achievements of technology got stuck? I draw hereto substantially on Henry Kissinger’s must read World Order.

In realism it is power that matters. The father of political realism, Thomas Hobbes was interpreted by Theodore Roosevelt to justify such politics: In new and wild communities where there is violence, an honest man must protect himself; and until other means of securing his safety are devised, it is both foolish and wicked to persuade him to surrender his arms while the men who are dangerous to the community retain theirs. For Roosevelt, if a nation was unable or unwilling to act to defend its own interests, it could not expect others to respect them. Liberal societies, Roosevelt believed, tended to underestimate the elements of antagonism and strife in international affairs. Implying a Darwinian concept of the survival of the fittest. Roosevelt’s favorite proverb was: Speak softly, but carry a big stick.

I understand that realism was a required form of governance at some stage of cultural evolution. But its seems more than necessary that mankind moves towards a new form of policy making. In political constructivism it is ideas which matter for ultimate success. The UN Climate Change Conference, which took place in late 2015 in Paris was such case of political constructivism. All 196 participating political entities signed the agreement on reducing environmental degradation. They did so under the enormous pressure of the challenge at hand and in the awareness that environmental protection is the only path forward. The agreement was signed though without being binding or containing any measures of execution. It is therefore important to realize like Stephen Stoft that weak agreements delay action until it may be too late.

It seems therefore to me that both realism and constructivism are flawed concepts when put forward alone. Realist politics will be always a power game, rarely focused on the general wellbeing; and constructivist politics mostly appear to be a douchebag waste of time. I argue for supplementing external policy with internal growth mechanisms, because a successful revolution requires the support of a society’s power structures and the continuous revolt of the involved individuals. Political revolutions do always lack continuous revolt of its adherents. I therefore do not agree with Hanna Arendt’s view that the French Revolution failed but the American succeeded. Both have failed as the upcoming presidential election and America’s decline into fascism will show.

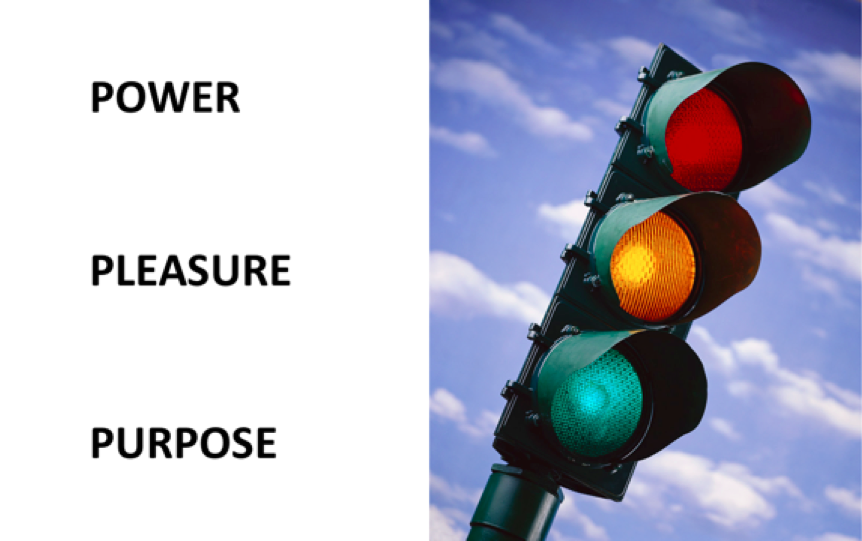

A succeeding revolution, I think, would be more like a spiritual movement; and I am not really convinced if such a movement is not doomed to fail as well, because man will be always tempted by power and pleasure at the expense of purpose. But at least it would teach its adherents emotional intelligence, compassion, empathy and last but not least sound and productive self-guidance. Power as a resource is therefore evenly distributed amongst all participants of a society. All these elements are neither program in US democratic lobbyism nor in Chinese totalitarian corruption. Both Xi Jinping and Donald Trump therefore mean for the world more of blind consumerism and devote citizenship.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed