| 181105_what_cant_be_remembered.pdf |

The last year has deprived us in an unprecedented city clean up from many beloved places and some familiar faces. A few of our favorite restaurants, my hairdresser and the mesmerizing Caojiadu bird- and flower market fell victim to a nationwide policy of pushing 1st tier city GDP growth. Our own apartment has been downsized due to the strict execution of fire safety regulations. And our daughter enjoyed her first military boot camp in her last year of Chinese public primary school. All this has made me think more than once if it’s still worth to stay, and every time I came to the conclusion that, yes, it is.

It was about half a year ago that I noticed subtle changes out in Qingpu, a large suburban district which borders Zhejiang and Jiangsu. It’s a bit of a hidden destination for water sport enthusiast. Sailors and kayaking afficionados flock to Dianshan Lake on weekends and during holidays to spend some time in nature and away from the concrete jungle. I have re-discovered the area for biking about a year ago and started to go there frequently for day and multiday biking trips. About half a year ago overnight stays for foreigners suddenly started to get more difficult. One had to register at the local PSB office with passport and event itinerary. About three months ago homestays and private B&B’s were then asked by police to decline accommodation to foreign guests, and eventually even Chinese guests were not any more allowed to stay overnight. I shared my house during one of my biking weekend with two Tongji university graduate students of urban planning who conduct research on how urbanization affects rural communities. They were surprised that regulations in rural Shanghai appeared to be stricter than in other Chinese provinces.

Things escalated when in August a bunch of families who had already check into their weekend homestay were forced by police to pack up, get in the middle of the night on their bus and return to downtown Shanghai. Hui Mengfan, the owner of the homestay, was furious when I talked to him. He had invested substantially in the renovation of desolate farm houses and runs his homestays for the growing customer segment of exhausted Shanghai urbanites. His business model combines countryside living with organic agriculture. His clients are invited to unwind in a village setting not far from the city center, eat healthy and fresh food, which he grows on a piece of land right next to his homestays. People love it and his places are booked weeks in advance for weekends and holidays.

I first thought that the muddy waters of economic reform in the Chinese countryside were cause for all the inconvenience. The Shanghai government seemed to be unclear about how to increase the rural GDP without jeopardizing its urbanization maxim. Quite a few homesteads had opened without proper business license, all of them operating in a grey zone; tolerated for economic growth, shunned for tax evasion and lack of government control. But then it dawned on me that there was something bigger happening in the background. The large scale preparation of some political ritual.

Eco-tourism entrepreneur Hui Mengfan continued his rant: “The police is ignorant of my business. Late summer and fall is my peak season and now they tell me that I can’t take in anymore guest until mid-November, when the China Import Expo is over.” I ask him how the trade fair is connected to his business. He starts to slowly shake his head in frustration: “Xidada will come to open the fair and they have to make sure that things are safe.” We continue to explore the reason for the measures and arrive at the conclusion that they are some sort of anti-terror policy to protect China’s president and other high ranking officials attending the trade fair. Some internal PSB directive seems to make all of Qingpu a red alert territory for the three months before the fair causing local police officers to close down private homestays.

Hui tells me only a few weeks later that rules have changed again. Chinese nationals are allowed to stay, foreigners continue to be ruled out. He receives instructions from the local PSB on a weekly basis and shrugs his shoulders with a typical mei banfa | that’s just how it is indicating the helplessness of laobaixing, i.e. people who have no say in government affairs. Sometime later over a cup of tea he confides to me: “Its quite scary that the entire local police administration scrambles forth and back only because XJP visits Shanghai. It feels like they are a flock of sheep who doesn’t know whether to run left or right when the wolf shows up.”

Native Culture and Global Trade

Zhong Binhua implanted that idea of the China Import Expo being a political ritual first into my small foreign mind. He runs a fuzzy nature & art commune at Dianshan Lake and desperately tries to find some way to get the municipal government fund his projects. He, too, operates in a grey zone, having neither a deed for his venue nor a business license for his events. But the government keeps supporting his folk art festivals featuring downtown and suburban, modern and traditional artists. The key word in all this is 本土文化 |native culture.

Having studied the cultural revolution back in school and listened to atrocious stories told by relatives the term evokes strange associations. There is the bright idea of maintaining and promoting local crafts, traditions and art, the idea of respecting and cherishing native culture. But there is also the dark element of turning small structured native culture into a standardized and tightly controlled top down product churned out by a government which has recognized that people need small structures to stay sane when communities increasingly get vaporized by the industrial revolution. American anthropologist and poet Gary Snyder would call this probably institutionalized wildness. Artist Suzanne Treister perceived the control society as the devil – no matter how it clads itself.

Zhong Binhua told me back in April that Qingpu bureaucrats had asked him after a successful event if he could also think of something similar for a larger audience. Only two weeks later he was euphorically telling me that the government had selected him to design a part of the opening ceremony for the China International Import Fair in November. Suddenly the jigsaw took shape and I saw the picture at large. An international trade fair to show off China’s traditional culture and a ground zero for a cyberleninist blend of tradition and modernity. That was a setup which tunes into what I have gathered till now from Beijing’s overarching political course.

How to Bridge Tradition and Modernity – and stay in control?

Kai Strittmatter, sinologist and Beijing correspondent of one of German’s most important newspapers, spoke earlier this year at the German Chamber Shanghai annual meeting to a large crowd about “The New China – How a country reinvents itself with big data, AI and a social credit system.” He shared his many insights of visiting China’s risen and rising tech stars and how they are locked into state controlled capitalism. What stuck with me is though his description of the perfect prison conceived by 18th century philosopher Jeremy Bentham.

The panopticon is a circular building with only one watchman in its center potentially observing all prison inmates simultaneously. It models the physical environment for a society with zero privacy. While Bentham himself had the idea with the reduction of administration and supervision expenses for England’s crammed penitentiary institutions, he thought of it also in terms of a power architecture and described the panopticon as "a new mode of obtaining power of mind over mind, in a quantity hitherto without example".

The idea of the panopticon was invoked by French philosopher Michel Foucault in Discipline and Punish almost two centuries later, as a metaphor for modern "disciplinary" societies and their pervasive inclination to observe and normalize. The Panopticon is an ideal architectural figure of modern disciplinary power. The Panopticon creates a consciousness of permanent visibility as a form of power, where no bars, chains, and heavy locks are necessary for domination any more. Instead of actual surveillance, the mere threat of surveillance is what disciplines society into behaving according to rules and norms.

Strittmatter who is about to leave China by the end of the year ended his presentation with a cryptic remark, “I don’t know what it is, but something very special is happening in present day China, something the world has never seen before, and I somehow regret to not be able to witness this in a front row seat.” The abundance of CCTV cameras on every building and street in rural Qingpu, the large monitor walls which are visible in the local PSB office, and the rediscovery of native traditional culture will be two essential pillars in this story.

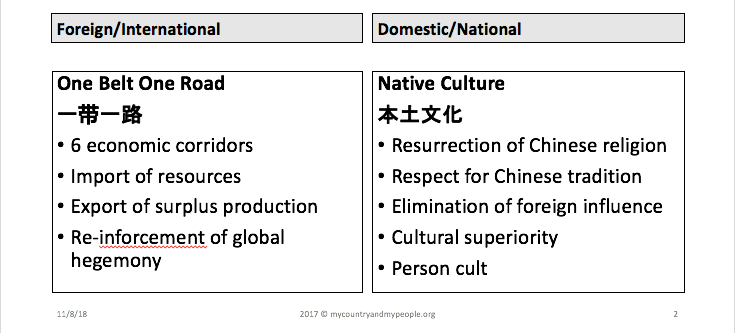

The Xi administration pursues since 2013 two flagship policies, one which cries to be heard by the entire planet, the other simmers silently behind the Great Wall. The 一带一路|One Belt One Road (OBOR) project is designed to turn Beijing into a 21st century Rome. It connects China through six economic corridors with the ROW and enables the Chinese empire with an infrastructure of roads, railways, sea- and airports to wield the same or even more power than Roman built roads did two millennia ago. There has been much discussion about the far objectives of the OBOR project, but there is a consensus that the infrastructure serves three main purposes:

- Export China’s surplus production and strengthen the domestic economy

- Import resources from all around the world in a magnitude and efficiency which renders global trade into a Chinese monopoly

- Strengthen the Middle Kingdom as global 21st century power center

Much has been written in the past years about pax sinica, China’s resurgence and the shift in of power in international relations. Martin Jacques was 2009 one of the first to capture the picture in When China Rules the World. Howard French was the last of the serious authors to comment on how China’s history defines our global future in Everything Under Heavens. But none of these rather political books has given me as much insight as Tomas Plaenker’s Landscapes of Chinese Souls: The Enduring Presence of the Cultural Revolution.

In contrast to the international or foreign flagship policy, the domestic flagship policy takes on a completely different subject: culture. There is no such thing as a catchy title like OBOR for this policy and that’s why it is so hard to make out. The keen observer and sturdy China watcher recognizes though a few patterns well known from cyclical Chinese history. One of cultural superiority. One of putting the Middle Kingdom in a class of its own and the ROW into a giant drawer labelled non-Chinese.

本土文化 | native culture or literally translated culture from this soil is a concept of many layers, but it’s above all one which aims at establishing a cultural purity, which makes it easy to differentiate what is Chinese and what is not. It seems that what Henry Kissinger described in World Order so typical for Russia in terms of territorial control is for the Chinese true in terms of cultural control. Kissinger explains that Russian governance is hard to understand, in particular for small European nation states, because it is defined by the constant fear of a large, sparsely inhabited territory breaking apart. The only possible response to this challenge was throughout the 19th century permanent expansion to counter implosion.

Chinese governance seems to apply the same concept in regard to culture since about two millennia. It was the early population density on the Chinese continent, the multitude of languages and the number of tribal kingdoms which forced Chinese rulers early on to establish one writing system and a single currency. China fared well with this approach and early on a sense of cultural superiority formed at the ruling courts, one which prevailed even if the ruling dynasty changed. It was a cultural superiority which blended religion and culture at a large or in other words, which understood religion as a subset of culture; something many modern thinkers are still not capable of doing. Culture became superior to biology. Customs more important than kinship. Behavior more important than DNA. Nurture more important than nature.

Modern neuroscience confirms what Chinese rulers seemingly know since centuries. It is the construction of a common cultural reality which bonds subjects into larger entities. For the ruler the nature and thus race of a person – a widely held belief in the decades preceding the two WW - ultimately doesn’t make a difference as long as the ruled pay due taxes and respect the prevalent hierarchy. In order to maintain such hierarchies it is though required to create a homogenous culture, one of harmony and peace, one which never questions the existing power structures. This is the essence of Confucianism, a doctrine of cultural unity, born out of a period of permanent war and destruction and limited or no social progress. Confucius conceived his teachings under the marring impression of a Zhou Empire which was about to break apart and into small thiefdoms and competing petty kingdoms. He thought of cultural unity and pruning as the only solution to achieve social progress and was perhaps a bit nostalgic of the early Spring and Autumn period, when the Zhou dynasty reigned supreme over the Chinese heartland.

That was 2500 years ago. Most of humanity was then organized in tribes, and even if part of a larger organizational form, local languages and customs prevailed. People lived on and off their land and despite their hardships they had a clear social micro-cosmos to navigate in. The West has since then brought the scientific and industrial revolution upon us – with all its blessings and curses. We have eliminated much disease and hunger from this planet, have delayed death substantially and have created a material affluence which has never been seen before. The industrial revolution has though also vaporized much of society as we knew it for millennia and has through nations, markets and technology standardized our cultures to such an extent that most global cities resemble each other to a far extent.

Under such general conditions it is highly questionable if political power should continue to seek the standardization of culture. Beijing has recognized this threat. Confucius is by some considered the father of sociology, although the modern discipline was only founded by people like Herbert Spencer, Max Weber or Emile Durkheim in the 19th century. This is no coincidence, because Chinese have always been far superior to the West in understanding the workings of societies and cultures. The main difference is though that the Chinese elite has kept these insights to itself up to this date, whereas the West has undergone a series of social revolutions which effectively lead to a wider dissemination of knowledge within society at large.

American author Ian Johnson described the resurrection of religion in his 2017 book The Souls of China as the central aspect of the Native Culture policy. It is a too remote concept for most foreign observers because we have been brainwashed for decades that China is an atheist and communist country, but all of a sudden we should believe that China has turned both religious and capitalist. Johnson explains XJP’s interest in religion like this:

Religion was [in ancient China] spread over every aspect of life like a fine membrane that held society together. MZD called divine authority one of the “four thick ropes” binding traditional society together; the other three were political authority, lineage authority, and patriarchy. A local temple could be like the cathedral and city hall of a medieval European town rolled in one. In the words of the historian Prasenjit Duara, religion was society’s “nexus of power.” But religion was more than a method for running China; it was the political system’s lifeblood. The emperor was the “Son of Heaven,” who presided over elaborate rituals that underscored his semi-divine nature. Officials duplicated many of his rites at the local level, especially by praying at temples to the local City God. From the fourteenth century onward, the government mandated that every district of the empire have its own City God temple [effectively a town hall to venerate the emperor].

It is under this light of Chinese history and the elite’s sociological understanding that the Native Culture policy has to be read. XJP started in 2013 to pour substantial amounts of tax money into the renovation of Buddhist, Taoist and Confucian temples. Shanghai’s Jingan Temple is only one of many elaborate projects with the far objective of tying the forth rope again around a society which is in a state of dissolution.

One might argue that there is no such thing like society in China. There was and still is only the ruler and the ruled and as such only the hierarchical relationship between the emperor and the subject, between father and son. China has never made this critical step in its social evolution or has it still ahead. It is ironically former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher who said in an interview that there is no such thing as society, and without doubt her governance style could very well be labelled neo-Confucianist, but she said so in response to an over-boarding welfare system which deprived people of their self-responsibility, and was such as a political direction which can only be taken when the society has already been recognized as entity in its own right. Chinese governance has up to this date not resolved the relationship between the ruler and the ruled and it is this critical transformation which drives Beijing into total surveillance.

Social evolution might nevertheless have different trajectories. There is no natural law which demands that China must follow the same route Western industrialized nations have taken. There is actually quite a bit to say against that route, but I will refrain from this discussion since there is so much to read about the failure of democracies and capitalism. If China will indeed be the place where something completely new will happen as journalist Kai Strittmatter cryptically said is still open. The odds look good that it will, and I have little doubt about it. Will it though be cultural progress or what social psychologists call collective regression is another question.

We can summarize that China’s ruling elite drives with the two discussed flagship policies the main dichotomy of the 21st century: globalism vs. localism. OBOR intends to further unify the global market and beyond that establish a new international political system. The Native Culture policy tries to counter the dissolution of small structured social entities; and China’s push to control the AI industry serves as technological platform to achieve what some discuss as cyberleninism: total political control through technology. We are left with the challenging task of interpreting these policies’ far end: are they motivated by purpose or power?

The China International Import Fair gives ample reason to ask this question. It is without doubt the 2018 flagship event of the XJP administration (despite so many more gargantuan conferences and projects) which sits at the confluence of both flagship policies. The many months-long preparations for this event and the way it was promoted both abroad and domestically give ample room for interpretation.

Let’s start with a closer look at the main CIIE poster which adorns the streets of many Chinese cities throughout the last weeks. Shanghai is shown as the focal point from which a yellow light radiates in circles out into the ROW gradually losing its strength and eventually subsiding to the general blue of the planet. The symbolism of such a statement is incredibly strong and loaded with history. It contains the message of the OBOR policy which channels six economic corridors back into China, but it also resembles the more than two millennia old concept of the Huayi distinction, which separated the world into Chinese and non-Chinese, into cultural superior people and barbarians.

Monumental infrastructure investments, which have turned Shanghai literally upside down can be interpreted as required preparations for a large event or as a well-orchestrated performance of power. Its thus quite plausible to ask if the CIIE is not rather an event which shows Chinese citizens their Emperor’s might. The trade fair complex in Shanghai’s suburban West close to Xujingdong metro station is of such vast dimensions that the pyramids of Gize pale in comparison. The adjacent real estate developments which include hotels and office buildings have created a new CBD in a city which already has more business hubs than any other urban area on this plane.

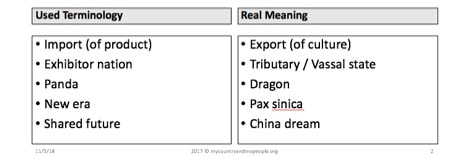

China’s rulers choose names carefully and quite often the words they choose indicate that exactly the opposite is meant. This tradition is embodied in a Chinese proverb: Pointing at a deer and calling it a horse. The CIIE is labelled as the first global import fair indicating a paradigm shift from China as export powerhouse to import destination number one. There is truth in this statement: Chinese consumers are wealthy and numerous. But it should be also read in exactly the other way, because the CIIE promotes the One Belt One Road policy and as such China’s hegemony to export not only its goods but also its values and culture throughout the world.

A historical interpretation would turn the foreign exhibitors into tributary and vassal states - yet another element in the traditional Chinese self-understanding as superior culture - which show through their participation that they kowtow to the superiority of their Chinese host and emperor with divine mandate to rule all under heaven. Considering that according to the state owned Xinhua news agency more than 130 countries, 3 international organizations and more than 3000 corporations will participate in the fair, XJP has succeeded to not only sell the fair as an event which will soften the trade balances with many guest countries, but also on a domestic level as a confirmation of China’s global leadership.

From a domestic point of view – let alone the obvious face lift of Shanghai’s urban landscape - the dramaturgy feels even more elaborate. I don’t know of any other country which shifts the holiday schedule for a capitalist trade fair. All but foreign schools and companies had to work the Saturday before the CIIE and then were granted an additional holiday on November 6 to spend time in massive traffic jams and multitudes queueing up to get into the trade fair or watch reporting about the fair and XJP’s opening speech on their TV sets. The CIIE is more than a trade fair, it is a ritual which celebrates capitalism as state religion and XJP as its pope, the son of heaven as the pope is called in Chinese tradition.

Historian Yuval Harari spoke earlier this year eloquently on the TED stage about the difference between nationalism and fascism. He describes nationalism as a healthy collective sentiment supporting social progress and contributing to the peaceful coherence of a society. He explained nationalism from the perspective of the citizen very much like Henry Kissinger did from the perspective of a statesman as a system of equal nations which respect each other’s borders, cultures and values. Harari defines fascism as disrespect of other’s nations, borders, cultures and values. He says: Fascism, in contrast [to nationalism], tells me that my nation is supreme, and that I have exclusive obligations towards it. I don't need to care about anybody or anything other than my nation.

For an Israeli nationalism might have a better connotation than for an Austrian and as such I do not agree to Harari’s definition. The ghost of nationalism has paved the road to the monster of fascism. Nationalism has rendered once multicultural areas of central and southeastern Europe into monolithic entities which lack the richness of their predecessor forms of organization. Israelis, more than any other ethnicity, think of nationalism probably as the driving force which gave them a home territory and this explains why Harari considers nationalism mostly as one of the vehicles which unify human beings in ever larger bodies (the other two being money and religion). He forgets though that nationalism and fascism are 19th century children from the same mother: technology supported power politics.

I don’t want to argue here with Harari, much of what he says is true and its probably just a question of perspective whether we want to see nationalism as something positive and fascism as purely negative. Both models of organization turn foul if they install a control society which does not allow wild, uncivilized and uncontrolled behavior - no matter if other nations are disrespected or not. Both models affect the human mind in a similar way: they reduce pluralism and biodiversity and as such deprive (human) nature from much of its richness which survives only in small structured forms of organizations.

The two lines of thought which I want to discuss her in the context of the CIIE are related to cultural superiority, a concept which is not well known in the west. Is cultural superiority the same as fascism and is a nation allowed to proselytize its culture? If we apply Harari’s definition of fascism and exchange the term with cultural superiority it would read like this: Cultural superiority, in contrast, tells me that my culture is supreme, and that I have exclusive obligations towards it. I don't need to care about anybody or anything other than my nation.

Most China watchers will now agree that China is a fascist civilization. Paired with the Confucian family system China is probably the prototype fascist nation and shares this assessment with Japan. But in an era of emerging globalism we also need to ask if a culture which drives the cutting edge of evolution has a sort of natural right to disseminate its values to turn into a regional or global Leitkultur, i.e. guiding ever larger numbers of people into a unified framework of behavior. So, perhaps, the CIIE should really be understood as the ROW kowtowing at the Chinese court, because this is what we have to do in the decades to come.

If the control society is though the devil as Suzanne Treister suggested, then a culture which pressures its way of living upon others who have not asked for such a blessing is something that needs to be avoided. We thus ought to observe closely what machine learning combined with power politics brings forward. It will through the arteries of the One Belt One Road initiative spread into our very own neighborhood. Bentham’s Panopticon foresaw a single watchman and is as such in an international context the opposite of what according to Kissinger the Westphalian Peace in 1648 established as a system of checks and balances between more or less equal players. The world order which we took for granted for almost four centuries is about to change and XJP seems to step up as a single watchman of whom we yet don’t know whether he is enlightened or corrupted. An enlightened watchman supported by modern technology would be indeed something novel, but as philosopher George Santayanas once said “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Further reading:

- On China being the cutting edge of human evolution

- On Shanghai’s urban facelift

- Jeremy Bentham’s ultimate prison design

- Roger Cremiers about China’s social credit system and cyberleninism

- On the One Belt One Road project in China’s Asia Dream

- On the resurrection of Chinese religion and socialist core values in Value Propaganda

- On cultural superiority in Hong Kong: Polis Between 2 Empires

- On the Chinese proverb: pointing at a deer and calling it a horse.

- Review of Henry Kissinger’s World Order

- Yuval Harari on the difference between nationalism and fascism

- Yuval Harari on the great divide between nationalism and globalism

- On why multicultural entities outperform monolithic nation states

RSS Feed

RSS Feed