There is also reason for concern that a cosmopolitan FT correspondent like Mr. Rachman does not dig deeper and tries to understand the roots of this self-isolation and by unearthing the roots, giving the reader more insights about the consequences of such regime behavior.

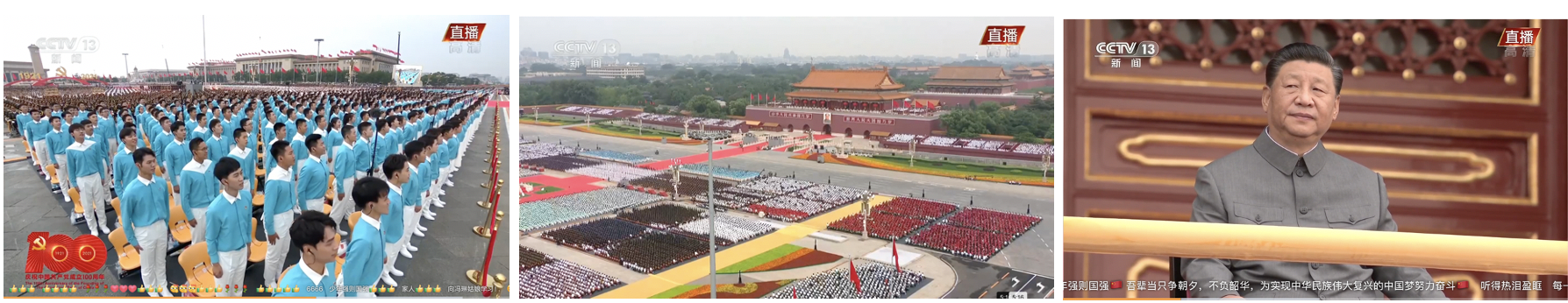

Since FT is restricted in access I copy Mr. Rachman's article here and ad a short video from my son's Chinese school. The Giant's Garden is a widely known primary school text. It is a fable about a Giant who denies children access to his garden and builds a wall around his estate to keep them out. Its a story which like no other explains the problem with China's self-understanding of cultural superiority and uniqueness.

Beijing’s zero-Covid policy is damaging international business and global governance

November 8, 2021 1:00 pm by Gideon Rachman

Xi’s dismissive attitude to the climate talks was not so much Middle Kingdom as middle finger. But the Chinese leader’s refusal to travel to Glasgow for COP26 — or to the G20 summit in Rome, before it — is part of a broader pattern of national self-isolation.

In response to the Covid-19 pandemic, China has installed one of the world’s strictest systems of border controls and quarantines. Foreigners or Chinese citizens entering the country must go into strict quarantine for a minimum of two weeks. Extra controls apply if they enter Beijing, where the leadership resides.

This system has in effect made it impossible for foreigners to visit China without staying for several months, or for most Chinese people to travel abroad. Xi himself has not left China for almost two years. The last time he saw a foreign leader in person was at a meeting with the president of Pakistan in Beijing in March 2020. Xi’s forthcoming summit with President Joe Biden will be held by video.

When much of the globe was in lockdown, the extreme nature of China’s measures seemed less remarkable. But as most of the world returns to something close to normality, China’s self-isolation is increasingly anomalous.

The effects on international business are already apparent. China continues to trade and invest with the outside world. But business ties are fraying. Foreign chambers of commerce in China report that international executives are leaving the country and not being replaced. Hong Kong’s role as a global business centre has taken a battering.

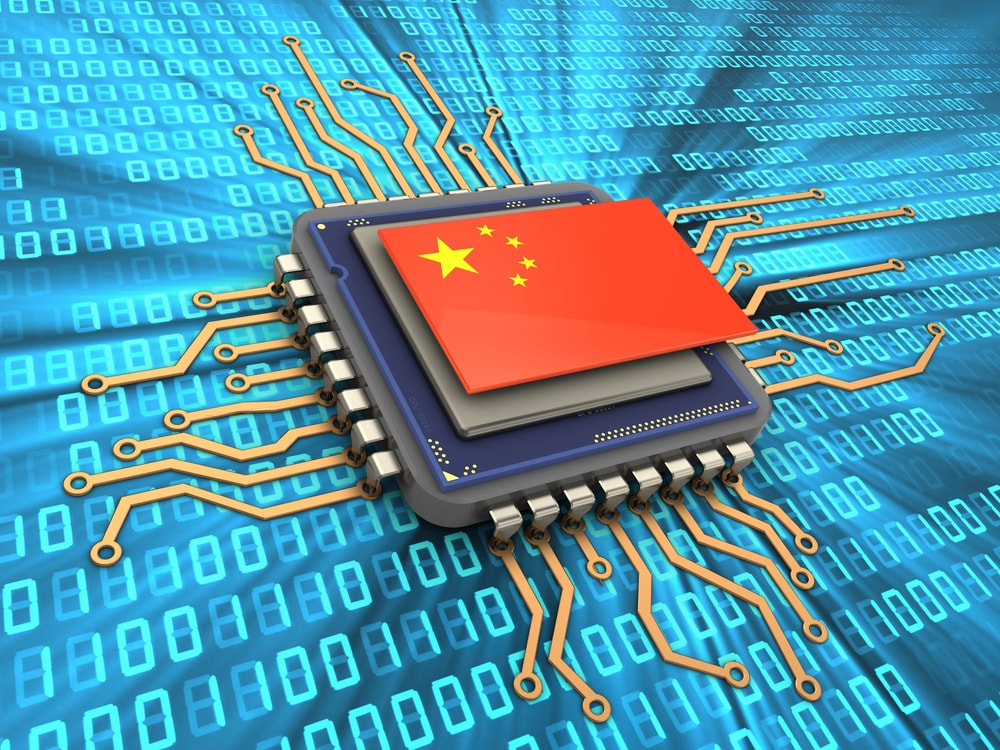

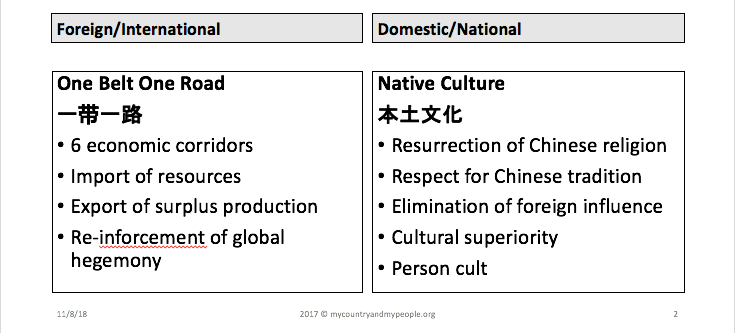

China’s leadership may actually welcome some of these developments. Yu Jie, a fellow at Chatham House in London, argues that the pandemic has allowed Xi to accelerate down a path where he was already heading — towards national self-reliance. That policy began well before the pandemic, with the “Made in China 2025” campaign, which promoted domestic technology and production.

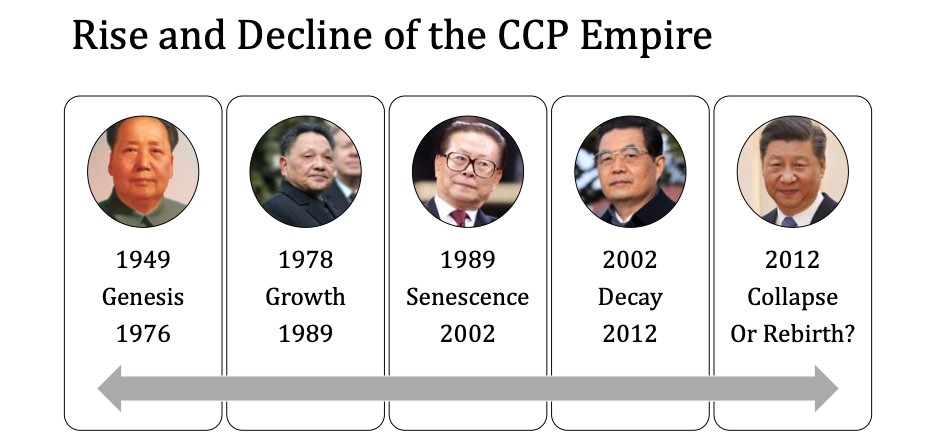

But with Covid-19, an emphasis on economic self-sufficiency has become a much broader inward turn — with dangerous implications for China and the world. China’s extraordinary rise over the past 40 years was triggered by Deng Xiaoping’s embrace of “reform and opening” in the 1980s. Deng saw that the isolation of Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution had led to poverty and backwardness. He was humble enough to realise that China could learn from the outside world.

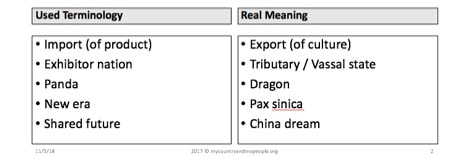

The current mood in China is very different. Rana Mitter, professor of Chinese history at Oxford, points to a danger that “closed borders will lead to closed minds”. After 40 years of rapid growth, China is self-confident.

The Chinese media portray the west, and the US in particular, as in inexorable decline. The Chinese government believes that the country is well ahead in some key technologies of the future, such as green tech and artificial intelligence. Beijing may believe that the world now needs China more than China needs the world.

Pandemic control has also become closely entangled with the political legitimacy of Xi and the Communist party. The official death toll in China is under 5,000, compared with 750,000 deaths in the US. The Xi government argues that while the US prates about human rights, the Chinese Communist party has actually protected its people.

But China’s zero-Covid policies now risk becoming a trap. As the outside world transitions towards living with low levels of the disease, contact with foreigners may look even more dangerous to China — leading to a renewed emphasis on restricting interaction with the outside world.

Even relaxing internal controls in China is difficult, since the Delta variant has led to small outbreaks of the disease in two-thirds of China’s provinces. Suppressing these outbreaks encourages the worst control-freak tendencies of the Communist party, which uses technology to monitor citizens ever more closely. In one episode, more than 30,000 people were locked inside Disneyland Shanghai and tested, after the discovery of a single case of Covid.

These kind of draconian policies are now causing some public debate in China. But controls are unlikely to be relaxed any time soon. This week the Communist party is holding a meeting that is preparing the ground for Xi to extend his period in power at a vital party congress in November 2022. The Chinese will not want to take any political risks before then. After the congress, China will be heading into winter when the disease can spike. As a result, many experts think that China’s zero-Covid policy — and the sealed borders that go with it — will extend well into 2023.

By that stage, China will have been in self-imposed isolation for more than three years. The Chinese and world economies are likely to suffer as a result, and so will global co-operation.

Yet the biggest and most intangible effect may be on the Chinese people. It is much easier to believe that foreigners are dangerous and decadent if you never meet them. When China eventually opens up, the world may encounter a much changed country.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed