I read his annual review for the first time last year and felt compelled to provide a glossed review to his 2021 observations reading them today. Dan, I hope you excuse that I quote some paragraphs of your ruminations directly - it puts my comments into context. And thank you for doing this - I have given up on my annual reviews already a few years ago.

Having lived myself in Shanghai for eleven years until a short while ago and being a frequent guest in Beijing, Tianjin, Wuhan, Guangzhou and Hongkong over the last decade, I share most of what Dan Wang wrote on the three Chinese metropolis areas. Beijing is mordor, sucking its hinterland dry in both ecological and metaphorical manner. It is a showcase for urban dystopia and what Schumacher called economics as if people didn't matter.

[...] The aura of state power is overbearing in Beijing. By power I mean the physical infrastructure, which is meant to intimidate. Beijing’s boulevards are so unwalkable because they are designed less for pedestrians than for army parades. [...]

[...] Beijing isn’t satisfied with greater national wealth. It is also seeking socialist modernization and the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese people.” That is a messianic drive, complete with sacred texts, elaborate rituals, and the occasional purge. [...]

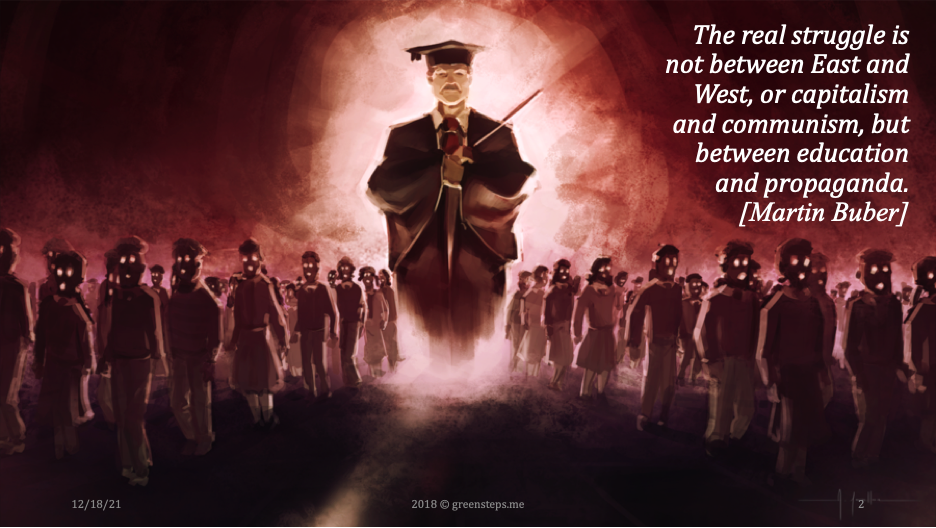

More sober and less outspoken China watchers call this messianic drive a renewed cultural revolution and an aspiration for world dominion with similar results: what can’t be remembered must repeat itself. highly recommended to read The Landscape of Chinese Souls on this subject.

[...] In spite of my physical dislike of Beijing as a city, I find myself sympathetic to its spirit. There is a use for the hard men of the north. I appreciate this line from Amia Srinivasan in Tyler’s interview this year: “One thing history might show us is that it is the prophets, and not the mere pragmatists, who are the most powerful world makers.” [...]

I have understood the word prophet always with a positive connotation. A prophet tries to help people out of misery and into utopia. Beijing's prophecy is double speak, because its prophecy is directed at a new in group which excludes in this religious nation myth 4/5th of humanity. Beijing lacks prophets unless Hitler was one. Dan cannot write this because he is still in China.

[...] Beijing’s goal is to channel entrepreneurial spirit towards useful goals. Profit cannot be the final standard of value, and the country’s best and brightest must work towards national salvation. I see that dynamic playing out in the regulatory campaigns this year. [...]

The most shocking event of 2021 was the national youth parade on July 1. Dan does not even mention it. It was a clear sign that Beijing goes down Berlin’s path with a century of delay. Whoever does not see this, is either blind or applies Chamberlain’s appeasement politics.

Shanghai is probably best as far as city life can go, but recent policies aiming at removing migrant workers and the insane clamp down since 2018 starting every year six months (!) before the Import Export Fair in Qingpu have made my home town pay such a heavy toll that I decided to leave for good. I share Dan's observation that Hong Kong is largely obsolete - how is that possible considering the marvelous setting of that city? A lesson for the non believers: the wrong from of government can turn Madeira into Alactraz.

Contrary to Dan, i did not change my residence much in China. I lived in Qiqihar, Kunming and Shanghai. I chose the periphery over the epicenters until i came in touch with Shanghai's gravity which is indeed 21st century New York, unless further tightening cuts it off from the rest of the world.

And there is a good reason to do so. Yuval Harari eloquently pointed at the intrinsic connection between science, technology and state power since the scientific revolution by showing how both religion and science get corrupted under power seeking institutional influence: In fact, neither science nor religion cares that much about the truth, hence they can easily compromise, coexist and even cooperate. Religion is interested above all in order. It aims to create and maintain the social structure. Science is interested above all in power. It aims to acquire the power to cure diseases, fight wars and produce food. As individuals, scientists and priests may give immense importance to the truth; but as collective institutions, science and religion prefer order and power over truth.

[...] I don’t think that Beijing’s primary goal is to reshuffle technological priorities. Instead, it is mostly a mix of a technocratic belief that reducing the power of platforms would help smaller companies as well as a desire to impose political control on big firms. [...]

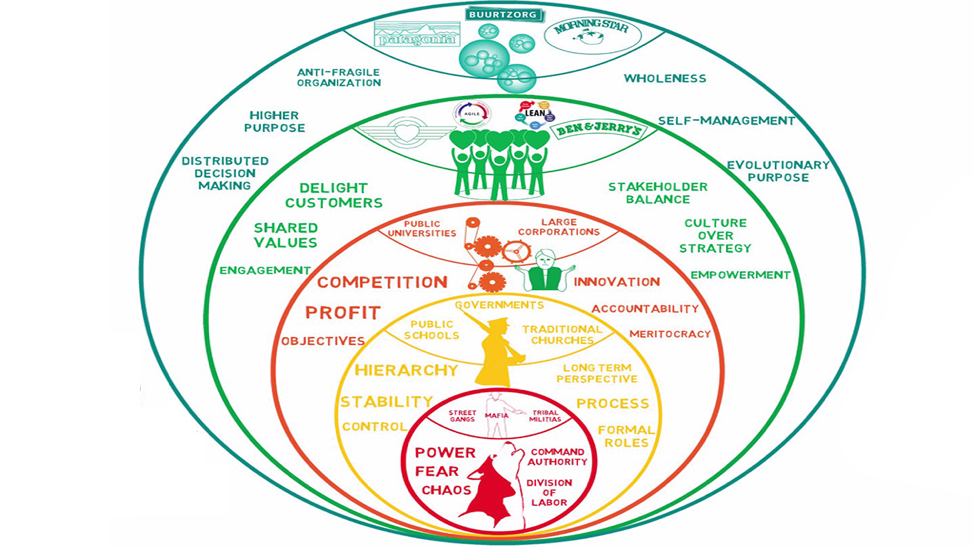

That’s blatant euphemism. Beijing is itself a state capitalist enterprise and its motivation in cracking down on platforms is strengthening its own sphere of influence. As the saying goes, 一山不容二虎 | there can’t be two tigers on one mountain. Beijing centralizes wherever possible and therefore turns into what Fritz Schumacher called big and ugly. Beijing is as a matter of fact the last stage in an organizational evolution which celebrates in the scheme of General Motors’ centralized decision making and was described by authors like Ken Wilber or Frederic Laloux as being obsolete.

What was the industry profiting from? In the government’s view, education companies have become adept at monetizing the status anxieties of parents: the Zhang family keeps feeling outspent by the Li family, and vice versa. In a similar theme, the leadership considers the peer-to-peer lending industry as well as Ant Financial to be sources of financial risks; and video games to be a source of social harm. These companies may be profitable, but entrepreneurial dynamism here is not a good thing. [...]

Every move that Beijing makes is ideological. Dan wrote himself a few paragraphs earlier that Beijing has a messianic drive, complete with sacred texts, elaborate rituals, and the occasional purge. The ideology which cyberleninist Beijing is enamored with is one of Chinese cultural superiority fueled by 百年国治 | 100 years of humiliation. It manifests itself domestically in the resurrection of Chinese religion and internationally through the 一带一路 | One Belt One Road policy.

It is important to recognize however that an orange leader perceives himself as last instance in anthropocentric hierarchy. Power supersedes truth. This is the reason why a potential decentralization and breakdown of the state education monopoly is viewed by Beijing as a direct threat which must be eliminated. What if students all over the country could decide where they get their brains washed and even worse with which detergent? A nightmare for Beijing‘s elite which needs enemies like the West or Japan to rally its troops.

Not everybody in a society of 1.4 billion can get a STEM PhD. A power-driven regime leaves behind 700 million rural Chinese who don’t have a part in the Chinese Dream and there is another narrative about China’s stellar rise which is told by people like Scott Rozelle, a Stanford economist who researches China’s health and education sector since more than two decades. Dan's observations are highly biased towards urban centers which are in Deng Xiaoping's words the places which need to get rich first | 一部分先富起来。

[...] It’s too early to tell if in a decade China will have fewer founders of Jack Ma’s daring. So far at least, entrepreneurial types around me have found his example too removed to be worth bother. [...] In this best case, Beijing would succeed at taming its robber barons without extinguishing dynamism in the following century. [...]

com’on. Beijing is the robber baron. political scientist Sebastian Heilmann made a good point in showing that there is only a thin line between organized crime and Far East Asian style state capitalism which instrumentalizes corporations for its own power goals.

[...] I expect that China will grow rich but remain culturally stunted. By my count, the country has produced two cultural works over the last four decades since reform and opening that have proved attractive to the rest of the world: the Three-Body Problem and TikTok. Even these demand qualifications. Three-Body is a work of genius, but it is still a niche product most confined to science-fiction lovers; and TikTok is in part an American product and doesn’t necessarily convey Chinese content. Even if we wave nuances aside, China’s cultural offering to the world has been meager. Never has any economy grown so much while producing so few cultural exports. Contrast that with Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, which have made new forms of art, music, movies, and TV shows that the rest of the world loves. [...]

This too is an interesting statement: does a civilization like China really have to produce any of the superficial cultural kitsch we know from the US? there is so much about Chinese culture which keeps the world in East and West enthralled. Tea rituals, Daoist philosophy, TCM, just to name a few. The Chinese have as social psychologist Lin Yutang once noted a penchant for pragmatism which most likely is the result of early overpopulation and a constant fight for survival. The fact that there was little space for fantasies and utopias is most prominently embodied in the teachings of Master Kongzi himself, who found no interest in transcendence as long as social life was disorganized and ravaged by war.

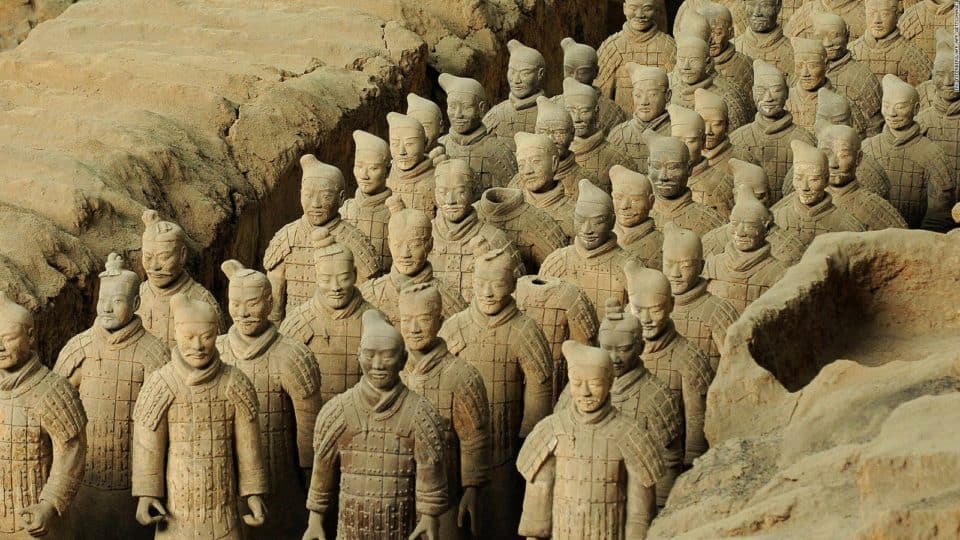

Fully agree on this paragraph and also with a government which endorses life in the physical world – the question is though if life is just a means to an end if yes, which end we spend it for. Another paranoid terracotta army potter does however not get my support.

[...] China is like the thinking ocean in Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris: a vast entity that produces observations personalized for every observer. These visions may be a self-defense mechanism, allowing leftists to see socialism and investors to see capitalism; or, as Lem’s ocean might be doing, China is vastly indifferent to foreign observers and generates visions to play with them. Whatever the case, we need a better understanding of this country. Too many commentators have been interested in the story of China’s collapse. When the collapse doesn’t come, they lose interest and move on. It’s a more important and more subtle skill to figure out how this country can succeed, because that is the exercise the Chinese leadership is engaged in. [...]

In an interconnected and globalized world that we live on, in an era that is called Anthropocene, if one country the size of China succeeds alone, it means that we fail as a species. The same might be true for China’s failure. The question is thus how we can succeed together.

[...] In 2018, I started to say to people that China would close its doors in 40 years, by the centenary of the country’s founding. At that point, the Celestial Empire would be secluded once more, while its people can be serenely untroubled by the turmoils of barbarians outside. Everyone reacted with disbelief, saying that there’s no way to shut down a country. But it looks like I was off only by the wrong centenary: China has been mostly shut in 2021, a hundred years after the party’s founding. I think that the government has no real exit plan for this pandemic. Any time it looks like it might relax, another variant shows up. The leadership probably has no firm aspiration to open the border at any date, and instead will assess the situation of variants and medical treatments every so often. If things don’t look good, then it won’t open up. [...]

Agreement here as well. I have been observing the Sakoku tendencies for a while and explained its ecological effects in a review of Evan Osnos’ Age of Ambition. That was about a year ago, when I first read and mostly disagreed with Dan’s annual review. Our affection for commenting on China is however such a broad common ground that I appreciate every disagreement as an invitation to contemplate a different perspective.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed